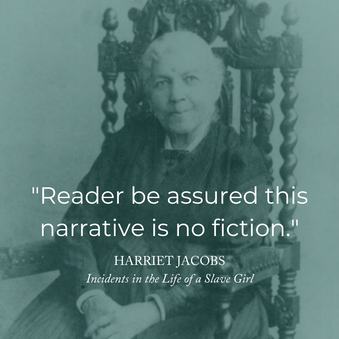

Visiting Harriet’s Literary Neighborhood #5: Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl5/1/2020 Dr. John Getz from Xavier University is leading us on a tour of Harriet's "Literary Neighborhood"--authors and work that interacted with her own life and work, even though they were often geographically far apart. CLICK HERE for the full series.  Harriet Beecher Stowe’s interaction with an aspiring African American woman writer didn’t go well. See what you think Harriet’s motives might have been. In 1852, the spectacular success of the book publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin had made Harriet famous. That same year, another Harriet--Harriet Jacobs—who had fled slavery saw her freedom purchased by her Northern employer and friend Cornelia Grinnell Willis. A year later, Jacobs was urged to tell her life story, which would provide a woman’s perspective on the full-length freedom narratives written by men like Frederick Douglass. Jacobs’s abolitionist friend Amy Post wrote to Beecher Stowe asking for advice and support for Jacobs’s effort. Instead of responding to Jacobs or Post, Beecher Stowe sent the letter to Willis, asking for verification and permission to use Jacobs’s story in A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which Beecher Stowe was currently writing. A Key was her documentary defense of the picture of slavery in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Jacobs was offended that Beecher Stowe had shared embarrassing details of her experience in slavery with Willis, who had not previously known that part of Jacobs’s history. Jacobs responded to Beecher Stowe that she wanted to tell her own story but would provide her with “some facts for her book.” Beecher Stowe never answered Jacobs’s letters. Was Beecher Stowe just too busy to take on another project? Did she suspect that Jacobs’s account of hiding seven years in an attic was based on Cassy’s stratagem in Chapter XXXIX of Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Even if she did, shouldn’t she have responded directly to Amy Post and Jacobs rather than to Willis? Biographer Joan Hedrick attributes Beecher Stowe’s treatment of Jacobs to “insensitivity bred by class and skin privilege . . . probably exacerbated by her sense of literary ‘ownership ‘ of the tale of the fugitive slave.” Jacobs was right to insist on writing her own story, which she did admirably over the next few years. It took her three more years, until 1861, to find a publisher. Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl powerfully reveals the double oppression faced by enslaved women while providing an inside look at the rich cultural network enslaved people nurtured to keep themselves alive. You can read Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl free online through Project Gutenberg. Please share your comments and questions on any part of Jacobs’s story or this tale of two Harriets. We’d be delighted to hear from you. About the author: Dr. John Getz, Professor Emeritus, Xavier University, retired in 2017 after teaching English there for 45 years. He specializes in American literature, especially nineteenth century, as well as the intersections of literature and peace studies. He has written articles on a variety of authors including Edith Wharton, Sherwood Anderson, and Ursula Le Guin. He appears in the documentary film Becoming Harriet Beecher Stowe, scheduled for release in spring 2020 by Fourth Wall Films.

2 Comments

Stephanie Peters

8/26/2022 01:15:12 pm

I just finished reading “Incidents in the life of a slave girl” and I absolutely loved it. It has become one of my favorite books. I have to admit I was a bit shocked when I read her account of how Harriet Beecher Stowe responded to her letter. I have yet to read Uncle Toms Cabin, but I imagined an abolitionist would have more respect for Harriet Jacobs story than to send her letter to her white friend in reply.

Reply

John Getz

8/29/2022 12:24:33 pm

Hi Stephanie,

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2025

Categories

All

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed