The 20th Century History of the House

Harriet's legacy continued into the 20th Century. The story of people helping one another and advocating for their rights is a large part of that tradition. We are continuing research in this area. Additions and updates will be posted periodically.

The Monfort Family Period

The House was purchased by Joseph G. Monfort in 1865. In the last decades of the 19th century it underwent several structural changes, including enclosing the remaining portions of the back verandah. The house underwent a major remodeling in 1908. This project included the removal of the original staircase, the addition of the grand staircase now in use, and the addition of the current bookstore room. New mantels and thin oak flooring were also added. After several generations of Monfort family members, the last Monfort resident was Mary Monfort. In the late 1920s, she moved out, setting the stage for its next incarnation.

The House was purchased by Joseph G. Monfort in 1865. In the last decades of the 19th century it underwent several structural changes, including enclosing the remaining portions of the back verandah. The house underwent a major remodeling in 1908. This project included the removal of the original staircase, the addition of the grand staircase now in use, and the addition of the current bookstore room. New mantels and thin oak flooring were also added. After several generations of Monfort family members, the last Monfort resident was Mary Monfort. In the late 1920s, she moved out, setting the stage for its next incarnation.

The Former Beecher Family Home Becomes the Edgemont Inn

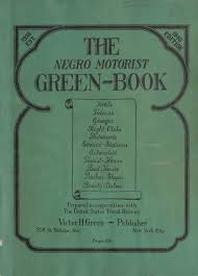

By the 1930s, the Walnut Hills neighborhood was a thriving African American business district. The House itself had become a boarding house and tavern. The Negro Green Motorist Book was developed by Victor Hugo Green in 1936 for African American motorists. Discrimination against African Americans meant that black motorists had trouble finding safe housing, restaurants, rest stops, and other accommodations. The Negro Motorist Green Book listed companies and organization that served and were safe for African Americans. It originally published safe havens in NYC, but then expanded to include all of North America. In the 1940 edition of the Green Motorist Book, the Harriet Beecher Stowe House then referred to as ‘The Edgemont Inn’, was one of only a few taverns listed as safe for African Americans in Cincinnati. Other Walnut Hills neighborhood businesses were also included as restaurants, hotels, and beauty parlors. The Edgemont Inn was listed in every edition from 1939 through the 1940s.

By the 1930s, the Walnut Hills neighborhood was a thriving African American business district. The House itself had become a boarding house and tavern. The Negro Green Motorist Book was developed by Victor Hugo Green in 1936 for African American motorists. Discrimination against African Americans meant that black motorists had trouble finding safe housing, restaurants, rest stops, and other accommodations. The Negro Motorist Green Book listed companies and organization that served and were safe for African Americans. It originally published safe havens in NYC, but then expanded to include all of North America. In the 1940 edition of the Green Motorist Book, the Harriet Beecher Stowe House then referred to as ‘The Edgemont Inn’, was one of only a few taverns listed as safe for African Americans in Cincinnati. Other Walnut Hills neighborhood businesses were also included as restaurants, hotels, and beauty parlors. The Edgemont Inn was listed in every edition from 1939 through the 1940s.

Members of the Harriet Beecher Stowe Home Memorial Association

Members of the Harriet Beecher Stowe Home Memorial Association

“A Lighthouse Symbolizing Good Will:” The Making of the Harriet Beecher Stowe House

During the years 1943-1949, the Harriet Beecher Stowe Home Memorial Association organized a campaign to buy and renovate the House and make it into a museum and community center. The Association acted out of concern for race relations and civil rights, and because they feared the house could lose its historic character and become a blight in the Walnut Hills neighborhood. The Association mobilized black residents and leaders in Walnut Hills and throughout the city, and allies among whites, and found crucial support from the Ohio Archaeological and Historical Society (now known as the Ohio History Connection or OHC). As the campaign progressed, the museum concept evolved and became focused on black history. The character of the Association as an interracial, interfaith, non-denominational movement, and the work of experienced leaders who drew upon multiple networks of influence, enabled the campaign to succeed. The core organizers played key roles as activists and leaders in the Association, utilizing their contacts in churches, fraternal groups, civil rights organizations, in politics and the law, and among club women. By the end of 1943, the Association had raised the money needed to buy the house. They continued fundraising efforts for renovation of the house and grounds. The Ohio House of Representatives appropriated some financing for the project as well. In 1949 the house was opened to the public as an Ohio historic site.

During the years 1943-1949, the Harriet Beecher Stowe Home Memorial Association organized a campaign to buy and renovate the House and make it into a museum and community center. The Association acted out of concern for race relations and civil rights, and because they feared the house could lose its historic character and become a blight in the Walnut Hills neighborhood. The Association mobilized black residents and leaders in Walnut Hills and throughout the city, and allies among whites, and found crucial support from the Ohio Archaeological and Historical Society (now known as the Ohio History Connection or OHC). As the campaign progressed, the museum concept evolved and became focused on black history. The character of the Association as an interracial, interfaith, non-denominational movement, and the work of experienced leaders who drew upon multiple networks of influence, enabled the campaign to succeed. The core organizers played key roles as activists and leaders in the Association, utilizing their contacts in churches, fraternal groups, civil rights organizations, in politics and the law, and among club women. By the end of 1943, the Association had raised the money needed to buy the house. They continued fundraising efforts for renovation of the house and grounds. The Ohio House of Representatives appropriated some financing for the project as well. In 1949 the house was opened to the public as an Ohio historic site.

George Wilson and the CCY

George Wilson and the CCY

Renovation Work During the 1970s

The Ohio Historical Society and the Citizen’s Committee on Youth (CCY) undertook a three-year rehabilitation project starting in October 1977. It was coordinated by George Wilson and included among other items installation of new restrooms, infill of windows on the north side of the building, addition of a new exterior fire escape, accessibility improvements. The CCY used youth workers aged 16 to 19 who were participating in a vocational training program. Photographs from this project show that it made significant changes to the House’s interior appearance.

The Ohio Historical Society and the Citizen’s Committee on Youth (CCY) undertook a three-year rehabilitation project starting in October 1977. It was coordinated by George Wilson and included among other items installation of new restrooms, infill of windows on the north side of the building, addition of a new exterior fire escape, accessibility improvements. The CCY used youth workers aged 16 to 19 who were participating in a vocational training program. Photographs from this project show that it made significant changes to the House’s interior appearance.

|

Web Hosting by iPage