Cincinnati Journal and Western Luminary Newspaper Collection

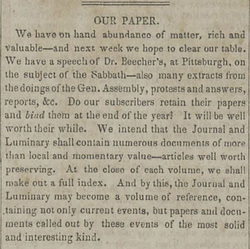

"Do our subscribers retain their papers and bind them at the end of the year! It will be well worth their while." -- Cincinnati Journal and Western Luminary, June 30, 1836

Befitting these instructions, the Stowe House possesses a bound collection of this Presbyterian newspaper featuring papers from the years 1836 and 1837. Selections from this collection are available on this website.

Download a PDF of this file.

Befitting these instructions, the Stowe House possesses a bound collection of this Presbyterian newspaper featuring papers from the years 1836 and 1837. Selections from this collection are available on this website.

Download a PDF of this file.

The Beechers and the Stowes in the Journal and Western Luminary

The papers at the Stowe House were probably owned by Professor Calvin Stowe, for his name was written on many of them-as you can see at the top of this page. Calvin Stowe as well as members of the Beecher family also frequently appeared in both the advertising and articles of this newspaper. Harriet went so far as to refer to the Journal as "our family newspaper."

In the July 28th, 1836, edition of the paper, for example, a reviewer gave glowing praise to Catharine Beecher's newly published Letters on the Difficulties of Religion. The work was labeled as a "beautiful little book, of exactly the right kind."

Download a PDF of the review here.

Read the Letters online at the Internet Archive.

The Lane Seminary, run by Lyman Beecher and including on its staff Calvin Stowe, also got its share of space in the paper. This glowing advertisement for the seminary ran for many months in 1837.

The papers at the Stowe House were probably owned by Professor Calvin Stowe, for his name was written on many of them-as you can see at the top of this page. Calvin Stowe as well as members of the Beecher family also frequently appeared in both the advertising and articles of this newspaper. Harriet went so far as to refer to the Journal as "our family newspaper."

In the July 28th, 1836, edition of the paper, for example, a reviewer gave glowing praise to Catharine Beecher's newly published Letters on the Difficulties of Religion. The work was labeled as a "beautiful little book, of exactly the right kind."

Download a PDF of the review here.

Read the Letters online at the Internet Archive.

The Lane Seminary, run by Lyman Beecher and including on its staff Calvin Stowe, also got its share of space in the paper. This glowing advertisement for the seminary ran for many months in 1837.

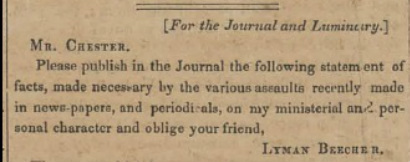

Dr. Beecher's Statement of Facts

On May 11, 1837, the editors of the Journal gave over a sizable portion of the newspaper’s space (nearly six entire columns) to a “Statement of Facts” from Lyman Beecher—Harriet’s assessment that the Journal was the Beecher-Stowe “family newspaper" had perhaps never been more accurate. The reasons behind the statement were many: the year 1837 was a difficult time to be Lyman Beecher and a complicated time to be a Presbyterian minister in the United States.

Due to another Cincinnati pastor’s disapproval of his relatively progressive theological views, Beecher had gone through two heresy trials within the Presbyterian Church in 1835 (and had been acquitted both times). The theological clashes within the Church that had led to the trials, however, were still growing: by 1837 the disputes had come to a head between the “Old School” (who were committed to orthodox Calvinism and did not support revivals and evangelism) and the “New School” (who favored a more progressive Calvinism and were proponents of the sort of revivals popular during the Second Great Awakening). In this very lengthy statement, Beecher attempted, among other concerns, to defend his name from some of the many accusations leveled against him. He also suggested that the Church must do all it can to keep itself in one piece.

Download a PDF of this Statement here.

Article date: Thursday, May 11, 1837

On May 11, 1837, the editors of the Journal gave over a sizable portion of the newspaper’s space (nearly six entire columns) to a “Statement of Facts” from Lyman Beecher—Harriet’s assessment that the Journal was the Beecher-Stowe “family newspaper" had perhaps never been more accurate. The reasons behind the statement were many: the year 1837 was a difficult time to be Lyman Beecher and a complicated time to be a Presbyterian minister in the United States.

Due to another Cincinnati pastor’s disapproval of his relatively progressive theological views, Beecher had gone through two heresy trials within the Presbyterian Church in 1835 (and had been acquitted both times). The theological clashes within the Church that had led to the trials, however, were still growing: by 1837 the disputes had come to a head between the “Old School” (who were committed to orthodox Calvinism and did not support revivals and evangelism) and the “New School” (who favored a more progressive Calvinism and were proponents of the sort of revivals popular during the Second Great Awakening). In this very lengthy statement, Beecher attempted, among other concerns, to defend his name from some of the many accusations leveled against him. He also suggested that the Church must do all it can to keep itself in one piece.

Download a PDF of this Statement here.

Article date: Thursday, May 11, 1837

Cincinnati Mobs of 1836 in the Paper

"A note of alarm for patriots" James Birney was an abolitionist who began publishing an abolitionist newspaper in Cincinnati in 1836. Twice in that year, during the nights of July 12th and July 30th, the offices of the paper were attacked. The Journal and Western Luminary was week after week highly critical of the mob violence that it saw as being rampant in the period, but at times the paper also criticized the abolitionists for supposedly inciting the violence. In the article that appears with this headline, rioters are called the “Robespierres of the country.” Download a PDF of this article. Article date: Thursday, August 4, 1836

Cincinnati's Response to the Mobs

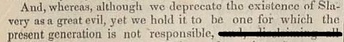

“And, whereas, although we deprecate the existence of Slavery as a great evil, yet we hold it to be one for which the present generation is not responsible…” Many Cincinnatians were not pleased by Birney's presence in their city. The newspaper covered a public meeting of powerful Cincinnati residents that took place in July 1836 in light of the Birney riots, in which those present passed resolutions to suppress abolitionist publishing. The men at the meeting also associated their cause--and its potential for vigilante justice--with the cause of the Boston Tea Partiers. The Journal and Western Luminary wrote that it was not yet going to comment on the results of this meeting, and instead it offered a letter to the editor that labeled the meeting results as "not the spirit of liberty, but of wanton reckless tyrany [sic]." Download a PDF of this article. Article date: Thursday, July 28, 1836 |

A Letter from "Franklin"

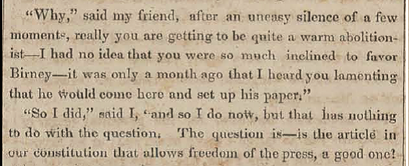

Harriet Beecher Stowe Comments on the 1836 Mobs “Why,” said my friend, after an uneasy silence of a few moments, really you are getting to be quite a warm abolitionist—I had no idea that you were so much inclined to favor Birney—it was only a month ago that I heard you lamenting that he would come here and set up his paper.” “So I did,” said I, “and so I do now, but that has nothing to do with the question. The question is—is the article in our constitution that allows freedom of the press, a good one!” In July 1836, Harriet was pregnant with twins and living in the Stowe House with other members of her family. This included her brother, Henry Ward Beecher, who was also temporarily serving as the editor of this newspaper at the time. Harriet here wrote to the editor as "Franklin" and retold a dinner conversation with a friend who was glad to hear of the destruction of James Birney's printing presses. The letter is certainly not explicitly abolitionist, but it effectively argues for freedom of the presses and condemns mob violence even when one is perhaps in agreement with the ends achieved. At the conclusion of the letter, the newspaper itself commented on the same subject. Download a PDF of this article. Article date: Thursday, July 21, 1836 |

Later Mob Violence

Death of the Reverend Elijah Lovejoy

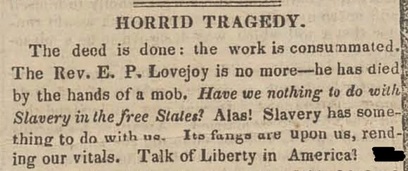

The Journal and Western Luminary had a generally passionate and excitable editorial tone, but perhaps no event covered in its pages inspired so much emotion as the 1837 murder of the Reverend Elijah Lovejoy. Lovejoy, like James Birney, was a noted abolitionist publisher. His anti-slavery newspaper, the Alton Observer, was published just across the river from St. Louis, MO, in Alton, IL. This did not sit well with proslavery Alton and St. Louis citizens. In November of 1837, an angry mob set fire to the warehouse holding Lovejoy and the printing press, shot Lovejoy, and destroyed his press in the river.

Unlike the Birney case, there was no ambiguity in the newspaper’s treatment of this mob violence. Lovejoy’s death was a “horrid tragedy” and the mob members “ruffians.” The Journal was also concerned about what this death meant for freedom of the press in the United States, asking “how has it come to pass in this country that men are denied the right of speaking and publishing on the subject of slavery…” (December 7).

The editors of the Journal felt so strongly about this issue that former subscribers to the Alton Observer who had now lost their paper were (beginning in December 1837) provided with an edition of the Journal bearing the name Alton Observer.

Download a PDF of the article announcing Lovejoy's death.

Article date: Thursday, November 16, 1837

Download a PDF of later comments on the events.

Article date: Thursday, November 23, 1837

Download another PDF of later comments on the events.

Article date: Thursday, December 7, 1837

Download a PDF of the article in which the Journal commits to providing the Observer.

Article date: Thursday, December 21, 1837

Death of the Reverend Elijah Lovejoy

The Journal and Western Luminary had a generally passionate and excitable editorial tone, but perhaps no event covered in its pages inspired so much emotion as the 1837 murder of the Reverend Elijah Lovejoy. Lovejoy, like James Birney, was a noted abolitionist publisher. His anti-slavery newspaper, the Alton Observer, was published just across the river from St. Louis, MO, in Alton, IL. This did not sit well with proslavery Alton and St. Louis citizens. In November of 1837, an angry mob set fire to the warehouse holding Lovejoy and the printing press, shot Lovejoy, and destroyed his press in the river.

Unlike the Birney case, there was no ambiguity in the newspaper’s treatment of this mob violence. Lovejoy’s death was a “horrid tragedy” and the mob members “ruffians.” The Journal was also concerned about what this death meant for freedom of the press in the United States, asking “how has it come to pass in this country that men are denied the right of speaking and publishing on the subject of slavery…” (December 7).

The editors of the Journal felt so strongly about this issue that former subscribers to the Alton Observer who had now lost their paper were (beginning in December 1837) provided with an edition of the Journal bearing the name Alton Observer.

Download a PDF of the article announcing Lovejoy's death.

Article date: Thursday, November 16, 1837

Download a PDF of later comments on the events.

Article date: Thursday, November 23, 1837

Download another PDF of later comments on the events.

Article date: Thursday, December 7, 1837

Download a PDF of the article in which the Journal commits to providing the Observer.

Article date: Thursday, December 21, 1837

Religious Interest Pieces

Travel Correspondence

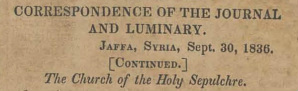

For several months in 1837, the newspaper ran a weekly column featuring correspondence of missionary traveler “P” in the Middle East. “P” spent quite a bit of time in places of religious significance, stating that he was eager to “visit the places so much referred to in the Holy Scriptures.” In one particular clipping, the author discussed a visit to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, believed by many to be the site of both Jesus’ resurrection and crucifixion. These visits to religious sites would have been particularly interesting to the generally devout readers of this paper, as it is unlikely very many of them would have been able to visit the region themselves.

Download a PDF of "P" explaining his intent to travel.

Article date: Thursday, April 13, 1837

Download a PDF of the account of the visit to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Article date: Thursday, April 27, 1837

Travel Correspondence

For several months in 1837, the newspaper ran a weekly column featuring correspondence of missionary traveler “P” in the Middle East. “P” spent quite a bit of time in places of religious significance, stating that he was eager to “visit the places so much referred to in the Holy Scriptures.” In one particular clipping, the author discussed a visit to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, believed by many to be the site of both Jesus’ resurrection and crucifixion. These visits to religious sites would have been particularly interesting to the generally devout readers of this paper, as it is unlikely very many of them would have been able to visit the region themselves.

Download a PDF of "P" explaining his intent to travel.

Article date: Thursday, April 13, 1837

Download a PDF of the account of the visit to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Article date: Thursday, April 27, 1837

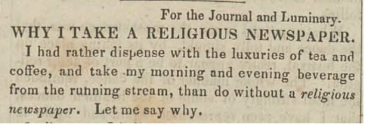

On Religious Newspapers

With print newspaper production and readership currently on a steady decline in the United States, it’s hard to imagine a time when small denominational religious newspapers could have attracted a large subscriber base. The readership of the Cincinnati Journal and Western Luminary was perhaps relatively small, but it was devoted to its paper. In this letter, the writer strongly defended his choice to continue paying for the Journal:

“Neither corn nor wine; neither the smiles of my wife, nor the prattle of my children, make me more glad, than the weekly visit of a neat, richly laden newspaper.”

Download a PDF of this letter.

Article date: Thursday, January 12, 1837

With print newspaper production and readership currently on a steady decline in the United States, it’s hard to imagine a time when small denominational religious newspapers could have attracted a large subscriber base. The readership of the Cincinnati Journal and Western Luminary was perhaps relatively small, but it was devoted to its paper. In this letter, the writer strongly defended his choice to continue paying for the Journal:

“Neither corn nor wine; neither the smiles of my wife, nor the prattle of my children, make me more glad, than the weekly visit of a neat, richly laden newspaper.”

Download a PDF of this letter.

Article date: Thursday, January 12, 1837

Comments on the General Assembly from the June 22, 1837 edition of the paper.

Comments on the General Assembly from the June 22, 1837 edition of the paper.

A Church Schism

As 1837 unfolded, the newspaper became increasingly consumed by the theological divisions taking place within the Presbyterian Church (PCUSA)--Lyman Beecher’s call for unity in May 1837 (see “Lyman Beecher’s Statement of Facts,” above) was going unheeded. The debates between the New School and Old School factions stemmed from a multitude of causes. The traditionalist Old School Presbyterians were more concerned with adherence to Church doctrine. They were also firmly against the kind of religious revivals that characterized the Second Great Awakening, and they didn’t believe in discussing matter that weren't strictly theological at general assemblies—specifically, they were unwilling to discuss slavery, while many New School Presbyterians were eager to explicitly condemn the institution.

A split was not far off: the last straw came at the 1837 General Assembly, when members of the Old School used their majority to rescind an earlier Plan of Union that had brought some Congregationalist congregations into the Presbyterian Church, arguing that doctrinal purity was at stake. Members of the New School were unhappy with this decision, but at the next year’s Assembly, they were prevented from even taking their seats to argue the issue. The Church was effectively divided. The New School and Old School each later separated once more over the issue of slavery, this time along geographical lines. Eventually, all the northern groups reunited as the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA) and the southern groups reunited as the Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS), but the PCUSA was never again in one piece.

The magnitude of this split was deeply felt in the newspaper, with pages of each edition for months devoted to the 1837 Assembly and its ramifications. The front page of every paper was devoted to a “Ladies’ Journal,” and in the July 13th edition of the paper, this element included a sort of non-apology for the recent space allotted to the General Assembly: “we would gladly have avoided it, but recent events left us no option.” The Journal condemned the actions of the Old School, claiming that the abrogation of the Plan of Union and the events of the General Assembly “would endanger all our institutions both civil and ecclesiastical.”

Download a PDF of the Ladies' Journal article on the split.

Thursday, July 13, 1837

Download a PDF of comments on the controversy from October 1837.

Article date: Thursday, October 26, 1837

Read the proceedings of the 1837 General Assembly online at the Internet Archive.

As 1837 unfolded, the newspaper became increasingly consumed by the theological divisions taking place within the Presbyterian Church (PCUSA)--Lyman Beecher’s call for unity in May 1837 (see “Lyman Beecher’s Statement of Facts,” above) was going unheeded. The debates between the New School and Old School factions stemmed from a multitude of causes. The traditionalist Old School Presbyterians were more concerned with adherence to Church doctrine. They were also firmly against the kind of religious revivals that characterized the Second Great Awakening, and they didn’t believe in discussing matter that weren't strictly theological at general assemblies—specifically, they were unwilling to discuss slavery, while many New School Presbyterians were eager to explicitly condemn the institution.

A split was not far off: the last straw came at the 1837 General Assembly, when members of the Old School used their majority to rescind an earlier Plan of Union that had brought some Congregationalist congregations into the Presbyterian Church, arguing that doctrinal purity was at stake. Members of the New School were unhappy with this decision, but at the next year’s Assembly, they were prevented from even taking their seats to argue the issue. The Church was effectively divided. The New School and Old School each later separated once more over the issue of slavery, this time along geographical lines. Eventually, all the northern groups reunited as the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA) and the southern groups reunited as the Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS), but the PCUSA was never again in one piece.

The magnitude of this split was deeply felt in the newspaper, with pages of each edition for months devoted to the 1837 Assembly and its ramifications. The front page of every paper was devoted to a “Ladies’ Journal,” and in the July 13th edition of the paper, this element included a sort of non-apology for the recent space allotted to the General Assembly: “we would gladly have avoided it, but recent events left us no option.” The Journal condemned the actions of the Old School, claiming that the abrogation of the Plan of Union and the events of the General Assembly “would endanger all our institutions both civil and ecclesiastical.”

Download a PDF of the Ladies' Journal article on the split.

Thursday, July 13, 1837

Download a PDF of comments on the controversy from October 1837.

Article date: Thursday, October 26, 1837

Read the proceedings of the 1837 General Assembly online at the Internet Archive.

19th-century Social Controversies

Women's Rights

While the Journal was quite progressive on the slavery question, the pages of the paper often printed articles on other subjects that point more towards the more typical conservative social views of the time. Women’s issues, in particular, were often treated in a traditionalist fashion. In October 1837, the newspaper reprinted an extract from Sarah Grimké’s Letters on the Equality of the Sexes and the Condition of Women that were at that time being published in the Spectator newspaper in Massachusetts. Grimké—a noted abolitionist and early feminist—held ideas were quite radical for the 1830s. In the extract printed, Grimké lauded historical European women who had led remarkable lives—including, for example, Vittoria Colonna, a widowed marchioness who became one of Italy’s most celebrated poets of the 1500s. Despite their probable agreement on abolition, the Journal here criticized Grimké, noting that her “attempt to break down the distinction between the province of men and women, is entitled to little commendation.” This criticism seems to be rooted in a fear of the disintegration of the family unit, as the writer claimed that if women occupy a sphere outside the home, “no ligaments can be found strong enough to bind together the restless spirits of men.” Indeed, this writer even envisions a dystopian future provoked by working women:

“If both the sexes are to occupy the same spheres, with the single exception of bodily labor, and, of course, to be engaged

in the same employments so far as physical strength will permit, there would remain no advantages from the formation of

different sexes, but the mere continuance of our race.—An iron age would come upon the world, destroying every earthly joy,

and making existence in this world, amidst the outbreakings of unrestrained and impetuous passions, but the prelude to the

madness and woe of the world of despair.”

Download a PDF of this article.

Article date: Thursday, October 26, 1837

Read the complete Letters on the Equality of the Sexes at the Internet Archive.

Women's Rights

While the Journal was quite progressive on the slavery question, the pages of the paper often printed articles on other subjects that point more towards the more typical conservative social views of the time. Women’s issues, in particular, were often treated in a traditionalist fashion. In October 1837, the newspaper reprinted an extract from Sarah Grimké’s Letters on the Equality of the Sexes and the Condition of Women that were at that time being published in the Spectator newspaper in Massachusetts. Grimké—a noted abolitionist and early feminist—held ideas were quite radical for the 1830s. In the extract printed, Grimké lauded historical European women who had led remarkable lives—including, for example, Vittoria Colonna, a widowed marchioness who became one of Italy’s most celebrated poets of the 1500s. Despite their probable agreement on abolition, the Journal here criticized Grimké, noting that her “attempt to break down the distinction between the province of men and women, is entitled to little commendation.” This criticism seems to be rooted in a fear of the disintegration of the family unit, as the writer claimed that if women occupy a sphere outside the home, “no ligaments can be found strong enough to bind together the restless spirits of men.” Indeed, this writer even envisions a dystopian future provoked by working women:

“If both the sexes are to occupy the same spheres, with the single exception of bodily labor, and, of course, to be engaged

in the same employments so far as physical strength will permit, there would remain no advantages from the formation of

different sexes, but the mere continuance of our race.—An iron age would come upon the world, destroying every earthly joy,

and making existence in this world, amidst the outbreakings of unrestrained and impetuous passions, but the prelude to the

madness and woe of the world of despair.”

Download a PDF of this article.

Article date: Thursday, October 26, 1837

Read the complete Letters on the Equality of the Sexes at the Internet Archive.

Temperance

The Journal and Western Luminary frequently included advertisements for temperance grocers—proprietors that supported the temperance movement and, of course, did not sell alcohol. The newspaper also supported temperance in other ways: in a letter, for example, a writer condemned the “grog shops” (grog referring originally to a mixture of rum and water consumed by sailors) supposedly being run by churchgoers in Cincinnati. Modern readers might be quick to view the newspaper’s wholehearted embrace of temperance as further evidence of an underlying conservatism. The temperance question, however, is not quite so simple. Many temperance activists, especially later in the 1800s, were also women’s rights reformers and abolitionists—all were “progressive” causes in the nineteenth century, as alcoholic husbands were seen as bad for women and families.

The editors’ perspectives on temperance are reflective of the complexity of their politics, but it should be no surprise that the Journal supported temperance movements. Lyman Beecher himself was a founder of the American Temperance Society, and Ohio would later in the nineteenth century become even more of a hotbed of temperance. Two of the biggest groups of the movement, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the Anti-Saloon League, were formed in the state. Many cities and counties in Ohio to this day place firm restrictions on the sale of alcohol—the city of Westerville, Ohio, the headquarters of the present incarnation of the Anti-Saloon League, did not become “wet” until 1995.

Download a PDF of the grog shop letter.

Article date: Thursday, August 10, 1837

Download a PDF of comments on temperance in Mason County, Kentucky.

Article date: Thursday, September 7, 1837

The Journal and Western Luminary frequently included advertisements for temperance grocers—proprietors that supported the temperance movement and, of course, did not sell alcohol. The newspaper also supported temperance in other ways: in a letter, for example, a writer condemned the “grog shops” (grog referring originally to a mixture of rum and water consumed by sailors) supposedly being run by churchgoers in Cincinnati. Modern readers might be quick to view the newspaper’s wholehearted embrace of temperance as further evidence of an underlying conservatism. The temperance question, however, is not quite so simple. Many temperance activists, especially later in the 1800s, were also women’s rights reformers and abolitionists—all were “progressive” causes in the nineteenth century, as alcoholic husbands were seen as bad for women and families.

The editors’ perspectives on temperance are reflective of the complexity of their politics, but it should be no surprise that the Journal supported temperance movements. Lyman Beecher himself was a founder of the American Temperance Society, and Ohio would later in the nineteenth century become even more of a hotbed of temperance. Two of the biggest groups of the movement, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the Anti-Saloon League, were formed in the state. Many cities and counties in Ohio to this day place firm restrictions on the sale of alcohol—the city of Westerville, Ohio, the headquarters of the present incarnation of the Anti-Saloon League, did not become “wet” until 1995.

Download a PDF of the grog shop letter.

Article date: Thursday, August 10, 1837

Download a PDF of comments on temperance in Mason County, Kentucky.

Article date: Thursday, September 7, 1837

National News

A Court Case

The newspaper also covered national affairs of note in its pages, sometimes reprinting articles from other sources with editorial commentary. A particularly striking example is a piece on an 1836 court case in Massachusetts where it was ruled that "a slave carried into that State by its owner, becomes en instanti free!" [sic]. The article was almost certainly referring to the case Commonwealth v. Aves, in which anti-slavery activists pushed for a suit against the owners of a slave girl named Med who had been brought into Massachusetts with them: they made the argument that since Med was in a free state, even only temporarily, she should not be allowed to be kept enslaved. Clearly, the activists emerged victorious, and Med was freed--though she tragically died in a Massachusetts orphanage only a short while later. This case was of critical importance in setting legal precedents about slaves brought into free territory for short periods. The Journal and Western Luminary made only a few carefully chosen comments:

"A slave case recently came up in Boston, which was decided in favor of the slave, and by which he [sic] was liberated.

The southern papers, even the religious, are much agitated about it. We extract from one, which plainly discovers the direction,

which efforts of the south are tending in the vexed question of Slavery."

Download a PDF of this article.

Article date: Thursday, September 29, 1836

A Court Case

The newspaper also covered national affairs of note in its pages, sometimes reprinting articles from other sources with editorial commentary. A particularly striking example is a piece on an 1836 court case in Massachusetts where it was ruled that "a slave carried into that State by its owner, becomes en instanti free!" [sic]. The article was almost certainly referring to the case Commonwealth v. Aves, in which anti-slavery activists pushed for a suit against the owners of a slave girl named Med who had been brought into Massachusetts with them: they made the argument that since Med was in a free state, even only temporarily, she should not be allowed to be kept enslaved. Clearly, the activists emerged victorious, and Med was freed--though she tragically died in a Massachusetts orphanage only a short while later. This case was of critical importance in setting legal precedents about slaves brought into free territory for short periods. The Journal and Western Luminary made only a few carefully chosen comments:

"A slave case recently came up in Boston, which was decided in favor of the slave, and by which he [sic] was liberated.

The southern papers, even the religious, are much agitated about it. We extract from one, which plainly discovers the direction,

which efforts of the south are tending in the vexed question of Slavery."

Download a PDF of this article.

Article date: Thursday, September 29, 1836

"The Emigrating Indians"

As illustrated by the clippings above, the Journal frequently included content and judgments on controversial issues of the day in its pages. Indian Removal—the infamous “Trail of Tears” of eastern Native Americans forced to relocate to Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma—was no exception. Here the newspaper reprinted a strongly-worded letter originally published in the Journal of Commerce (a publication that exists to this day). This particular writer condemned the removal and expressed great empathy for the Native peoples, stating that “no portion of our American history can furnish a paralel [sic] to the misery and suffering at present endured by the emigrating Creeks.” This perspective was relatively unusual for the time period, but one should not be too surprised to find it in this Presbyterian publication. Many Christians had always strongly opposed the Indian Removal Act, the 1830 law that originally allowed the President (then Andrew Jackson) to “negotiate” with Native tribes for their removal.

"The American people, it is presumed, are yet unacquainted with the condition of these people, and it is to be hoped

when they do become acquainted with the facts, the philanthropic portion of the community will not be found wanting

in their efforts to alleviate, as far as practicable, their extreme suffering."

Download a PDF of this article.

Article date: Thursday, April 13, 1837

As illustrated by the clippings above, the Journal frequently included content and judgments on controversial issues of the day in its pages. Indian Removal—the infamous “Trail of Tears” of eastern Native Americans forced to relocate to Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma—was no exception. Here the newspaper reprinted a strongly-worded letter originally published in the Journal of Commerce (a publication that exists to this day). This particular writer condemned the removal and expressed great empathy for the Native peoples, stating that “no portion of our American history can furnish a paralel [sic] to the misery and suffering at present endured by the emigrating Creeks.” This perspective was relatively unusual for the time period, but one should not be too surprised to find it in this Presbyterian publication. Many Christians had always strongly opposed the Indian Removal Act, the 1830 law that originally allowed the President (then Andrew Jackson) to “negotiate” with Native tribes for their removal.

"The American people, it is presumed, are yet unacquainted with the condition of these people, and it is to be hoped

when they do become acquainted with the facts, the philanthropic portion of the community will not be found wanting

in their efforts to alleviate, as far as practicable, their extreme suffering."

Download a PDF of this article.

Article date: Thursday, April 13, 1837

|

Web Hosting by iPage