The Civil War was fought between 1861 and 1865. Ultimately, the main reason for the war was slavery, but it is important to remember that when the North entered the war, its only goal was to restore the Union. While Harriet’s novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, had stirred up anti-slavery opinions in the North and was one of the main contributing factors to the war, not everyone in the North was united against slavery. During the Civil War, another question was the involvement of European powers such as Great Britain and France, specifically Great Britain. Even though Queen Victoria had declared neutrality in the affairs of the United and Confederate States of America, many British citizens supported the Confederacy in the form of funds and other things. In fact, the majority of the Confederate fleet was produced in Britain. Intervention by the British was a serious threat to the Union. Prior to and during the Civil War, Harriet resolved to both spread and sustain anti-slavery ideas in the American and English populace. As the New England Quarterly writes, “Convincing both the American and the English people that the Union cause centered on antislavery became, for Harriet Beecher Stowe, a moral crusade.” Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published in 1852 (note that this is the completed book, as the story itself was first published in serialized form in the National Era). Uncle Tom’s Cabin spread anti-slavery ideas throughout Britain and the United States. Englishwomen were quite touched by Uncle Tom’s Cabin and recognized Harriet with respect and fame as she journeyed across Europe in 1853. In fact, these women were so moved by Harriet and anti-slavery that 562,448 women signed “An Affectionate and Christian Address of Many Thousands of Women of Great Britain and Ireland to Their Sisters, the Women of the United States of America”, also known as the Stafford House Address. In the Stafford House Address, which was written at one of the homes of the Duke and Duchess of Sutherland (Scotland), the women pledged their support and stated that slavery must be ended. Between 1853 and the outbreak of the Civil War, Harriet continued to write articles and even another novel against slavery. The novel was titled Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp. She gained a column on the New York paper, the Independent. When war broke out between the United and Confederate States of America, Harriet saw the Civil War as a “holy crusade to emancipate the slaves,” Harriet saw the war as “part of the last struggle for liberty-the American share.” Harriet was very surprised when she found out that many English placed their support with the Confederacy. Few in Britain actually thought the war was about slavery. At the same time, most of the people in the Union did not think that the Civil War was to free the slaves. As a response to Confederate support in Britain, Harriet decided to write Lord Shaftesbury, a new supporter of the confederacy since playing a key role in the “Stafford House Address.” Harriet wrote of the North’s true goal, abolishing slavery. This letter was widely circulated. Her letter was met with a surprising amount of criticism in both Britain and the United States and failed to convince anyone of the abolitionist nature of the war. In 1862, Lincoln announced the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which was due to come into effect on January 1st of the following year. However, Harriet was still quite skeptical of Lincoln, especially after he removed General Frémont, who went above the law by freeing slaves without Lincoln’s approval. Harriet then decided to use the Proclamation as the basis for a “reply” to the Stafford House address. Around this time, Harriet went on a trip to Washington D.C, with a stop in Brooklyn to visit her brother. In Brooklyn, Harriet and her brother, Henry Ward Beecher, then asked Mrs. Lincoln (who was also visiting New York) if Harriet could meet the President while in the Capitol. Harriet did end up meeting Lincoln while in the capital. It was here that Lincoln issued the famous statement, “Is this the little woman who made this great war?” In this meeting with Lincoln, Harriet was assured of the President’s abolitionist devotion, and assured that he would sign the Proclamation fully. Harriet stayed in Washington for a little bit longer, completing her reply to the Stafford House Address. This was published in the Atlantic Monthly. Harriet’s “Reply” was quickly spread throughout Britain. While it was still criticized, the “Reply” managed to further convince the British that the Civil War was one against slavery. This, along with the Emancipation Proclamation, helped to further cement Britain’s further non-involvement in the war. On January 1st, 1863, Harriet attended a special concert to celebrate the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. Post celebration concert, Harriet resolved to let Lincoln guide the war, since she had already spoken to the British. Harriet returned to “a quieter life.” She no longer wrote articles focusing on anti-slavery. Harriet stopped writing articles for the Independent, and instead wrote a few articles on domestic ideas for the Atlantic Monthly. She desired and wrote about the “talk of common things.” Harriet once again returned to writing novels and spending time with her family. All quotes are from The New England Quarterly, unless stated otherwise. Primary Source: Other Sources:

About the author:

Emmett Looman is a Youth Docent at the Harriet Beecher Stowe House in Cincinnati. He enjoys history and is always happy to learn new interesting facts about the past.

0 Comments

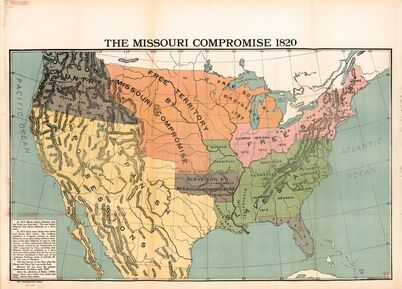

Source: Library of Congress Source: Library of Congress The nineteenth century saw the number of states admitted to the Union increase and along with them a number of measures affecting slavery. Debates over how to deal with slavery in new states and territories generated new laws and challenges to personal freedom. In 1803 Congress approved President Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase from France virtually doubling the nation’s size. In 1807, Congress banned the importation of slaves into the United States although this resulted in an increase in domestic slave trading in the South. In 1812, Louisiana became the first state created from the Louisiana Purchase entering the Union as a slave state. Pro- and anti-slavery passions were inflamed and skillful diplomacy and compromise were essential. For only a short while they prevailed. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 was an effort to preserve the balance of power between pro- and anti-slavery factions in the United States Congress. In 1820 Maine entered the Union as the 12th “free” state joining Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Vermont, and New Hampshire. The eleven slaveholding states were Kentucky, Tennessee, Maryland, Virginia, Delaware, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi. In 1821, Missouri entered the Union as the nation’s 24th state and the 12th slave-holding state, thus maintaining the balance of slave and free states. An essential element of this compromise was the amendment authored by Senator Jesse B. Thomas of Illinois: "And be it further enacted, That in all that territory ceded by France to the United States, under the name of Louisiana, which lies north of thirty-six degrees and thirty minutes north latitude, excepting only such part thereof as is included within the limits of the State contemplated by this act (Missouri), slavery and involuntary servitude, otherwise than in the punishment crimes whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall be and is hereby forever prohibited: Provided, always, That any person escaping into the same from whom labor and service is lawfully claimed in any other State or Territory of the United States, such a fugitive may be lawfully reclaimed, and conveyed to the person claiming his or her labor or service as aforesaid.” With the exception of Missouri, the proposed amendment established Arkansas’s northern border as the northern limit for slavery to be legal in the western territories. The 16th United States Congress passed the legislation on March 3, 1820, and President James Monroe signed it three days later. Lyman Beecher, Harriet’s father, achieved some degree of notoriety as he publicly preached against slavery in reply to the compromise. As a youngster Harriet overhead conversations about the compromise in her household. After Missouri's admission to the Union in 1821, no other states were admitted until 1836 when Arkansas became a slave state, followed by Michigan in 1837 as a free state. In the 1840s, Florida and Texas were admitted as slave states, and Wisconsin and Iowa as free states. The Missouri Compromise was effectively repealed in 1854 by The Kansas–Nebraska Act, which allowed the people of Kansas and Nebraska to decide whether they would enter the union as a free or slave state. In 1857, the antislavery provision of the compromise was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in the infamous Dred Scott versus Sanford case. Sources:

About the author:

Dr. Nicholas Andreadis is a volunteer at the Harriet Beecher Stowe House. He was a professor and dean at Western Michigan University prior to moving to Cincinnati. Prior to the American Revolution there was no provision to compel any North American colony to capture and return fugitive slaves from another colony. English court decisions and opinions came down on both sides of the issue. Some clarity was achieved with the 1772 decision in Somerset versus Stewart. Charles Stewart purchased the enslaved James Somerset in the colonial city of Boston. Stewart brought Somerset to England in 1769 but two years later Somerset escaped. He was recaptured and Stewart had him imprisoned on the ship Ann and Mary and directed that Somerset be sold to a plantation. Somerset's three godparents filed a writ of habeas corpus before the Court of the King’s Bench, which had to determine whether his imprisonment was lawful. The court narrowly held that, “ A master could not seize a slave in England and detain him preparatory to sending him out of the realm to be sold and that habeas corpus was a constitutional right available to slaves to forestall such seizure, deportation and sale because they were not chattel, or mere property, they were servants and thus persons invested with certain (but certainly limited) constitutional protections”. The Somerset judgment did not affect the colonies directly but the Somerset precedent was a warning to American slaveholders. On September 9, 1776, the Continental Congress formally declared the name of the new nation to be the “United States of America”. The Continental Congress had little interest in addressing either the slave trade or fugitive slaves. The Northwest Ordinance adopted in 1787 provided a method for admitting new states to the Union, subsequently Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin and Michigan. Article 6 of the Ordinance declared that there shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the territory. However, it clearly stated that any person escaping into the territory from whom labor or service is lawfully claimed in any one of the original states may be lawfully returned to the person claiming his or her labor or service. Thus the language of the ordinance prohibited slavery but also contained a clear fugitive slave clause as well.  In autumn 1787 The Articles of Confederation evolved into the Constitution. The status of slavery in the United States was a major impediment to ratification and resulted in the first of many debates and constitutional compromises. What emerged from their deliberations was the Fugitive Slave Clause in Article IV, Section 2: No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due. Consistent with this constitutional clause, Congress passed the first Fugitive Slave Law in 1793. The following is an example of how the FSA was implemented: A slave-owner or his agent could reclaim an alleged fugitive either by arrest on the spot or by securing a warrant beforehand. The case for removal would be heard by a federal judge or a court-appointed federal commissioner, who would be paid ten-dollars if a certificate of removal was issued, or five-dollars if the claim was denied. Slave testimony was prohibited, no jury was seated, the verdict could not be appealed, and other courts or magistrates were barred from postponing or overriding an order to remand the defendant into the custody of the claimant. The commissioner could authorize special deputies, or a citizen’s posse to accompany the fugitive’s return if the claimant feared an attempt to liberate the fugitive during the return. Stiff penalties of up to $500 fine were mandated for anyone aiding the escape of a fugitive or interfering with his/her return. Not surprisedly anti-slavery advocates denounced the 1793 law as a “kidnapping machine.” The law was affirmed and strengthened in 1850, angering many Northerners including Harriet Beecher Stowe. References:

About the author:

Dr. Nicholas Andreadis is a volunteer at the Harriet Beecher Stowe House. He was a professor and dean at Western Michigan University prior to moving to Cincinnati. Wondering what to read next? Wish you had paid more attention in literature class? Didn't get a chance to go to literature class? Pick something from this list and share what you think in over in our new Facebook group Harriet Beecher Stowe House Community Connection. Perspectives from the Eighteenth Century (1700s)

The Nineteenth Century (1800s) A Native American Autobiography William Apess, A Son of the Forest (1829) Transcendentalism Transcendentalism is the belief that the world we experience through our senses is less real than and only a symbol of the spiritual world behind it. In our best moments, we “transcend” (literally, “go across”) to that spiritual realm. Experiencing great (transcendentalist) literature can be a way to do that.

The American Romance “Romance” in this sense refers to fiction that deals with the unusual, even the extraordinary, in character and event, described in poetic language; it’s the opposite of realism, which becomes the dominant form in American fiction after the Civil War, although elements of the romance remain even in those texts.

Two Very Different Poets

“When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d” (1865)

Funeral in my Brain,” (1862), “After great pain, a formal feeling comes – ” (1862), “One need not be a Chamber – to be Haunted – “ (1862), “The Soul selects her own Society – “ (1862), “Because I could not stop for Death – “ (1862), “I heard a Fly buzz – when I died – “ (1863), “Much Madness is divinest Sense – “ (1863), “Publication – is the Auction” (1863), “A narrow Fellow in the Grass” (1865), “Tell all the truth but tell it slant – “ (1872) Focus on Slavery (the central problem of the US)

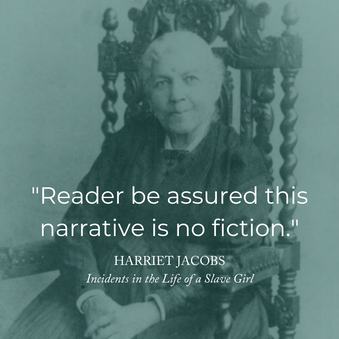

Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861)

Post-Civil War: The Age of Realism In literature realism is the opposite of romance. Realistic fiction tells stories about the ordinary in character and event in simpler, direct language. Of course, there are always exceptions, and romance elements remain in some of these works.

The Beginning of Naturalism Naturalism in fiction that explores the possibility that heredity and environment are such powerful influences that we may have no free will. Stephen Crane, The Red Badge of Courage (1895) and “The Veteran” (1896). If you’re burned out on Red Badge, you could read Crane’s 1893 novella Maggie: A Girl of the Streets or his great short stories “The Open Boat,” (1897), “The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky” (1898), and “The Blue Hotel” (1898). The last one was made into an excellent movie in the 1977 American Short Story Series for PBS. Bonus pick: My favorite book on American culture is Robert Bellah et al., Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life (1985, 1996, 2007). The insights in this book are still timely. If you read the prefaces and the first 84 pages of the text, you’ll have the basic argument and some useful terminology and a good perspective for analyzing American literature and culture. About the author:

Dr. John Getz, Professor Emeritus, Xavier University, retired in 2017 after teaching English there for 45 years. He specializes in American literature, especially nineteenth century, as well as the intersections of literature and peace studies. He has written articles on a variety of authors including Edith Wharton, Sherwood Anderson, and Ursula Le Guin. He appears in the documentary film Becoming Harriet Beecher Stowe, scheduled for release in spring 2020 by Fourth Wall Films. Visiting Harriet’s Literary Neighborhood #6: Rebecca Harding Davis, Life in the Iron Mills5/8/2020 Dr. John Getz from Xavier University is leading us on a tour of Harriet's "Literary Neighborhood"--authors and work that interacted with her own life and work, even though they were often geographically far apart. CLICK HERE for the full series.  Thanks to the amazing success of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1852, Harriet Beecher Stowe was considered one of the major authors of the day. She was important enough to be one of the founders of a prestigious new magazine of literature and culture, The Atlantic Monthly, in 1857. Four years later that magazine published the novella Life in the Iron Mills, launching the writing career of young Rebecca Harding from Wheeling in what was then Virginia. In 1863, that young author, in the midst of a productive decade of novel writing, married and became Rebecca Harding Davis. Scholar David Reynolds lists Davis with Emily Dickinson, Louisa May Alcott, and others in what he calls the American Women’s Renaissance from 1855 to 1865. But as the 1860s drew to a close, a strong backlash against the success of women authors, including Davis and even Harriet herself, was starting. Harriet wrote letters protesting hostile reviews of both their works and invited Davis to write for Hearth and Home, a monthly magazine Harriet was co-editing. Davis accepted. The backlash against women authors continued, and Life in the Iron Mills fell into obscurity until fiction writer Tillie Olsen rediscovered it and convinced The Feminist Press to reprint it in 1972. More than a century had passed since its original publication. Life in the Iron Mills is written in the poetic, symbolic style of Davis’s day, and the benevolent Quaker woman and her community at the end may remind you of Rachel Halliday and her family in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. But Davis’s subject—the plight of immigrants and the working class as the US industrialized—looks forward to the realism that would dominate American fiction after the Civil War and even to the naturalism that would appear in the 1890s. You can read this groundbreaking novella free online through Project Gutenberg. We welcome your questions and comments about your reading experience. About the author: Dr. John Getz, Professor Emeritus, Xavier University, retired in 2017 after teaching English there for 45 years. He specializes in American literature, especially nineteenth century, as well as the intersections of literature and peace studies. He has written articles on a variety of authors including Edith Wharton, Sherwood Anderson, and Ursula Le Guin. He appears in the documentary film Becoming Harriet Beecher Stowe, scheduled for release in spring 2020 by Fourth Wall Films. Visiting Harriet’s Literary Neighborhood #5: Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl5/1/2020 Dr. John Getz from Xavier University is leading us on a tour of Harriet's "Literary Neighborhood"--authors and work that interacted with her own life and work, even though they were often geographically far apart. CLICK HERE for the full series.  Harriet Beecher Stowe’s interaction with an aspiring African American woman writer didn’t go well. See what you think Harriet’s motives might have been. In 1852, the spectacular success of the book publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin had made Harriet famous. That same year, another Harriet--Harriet Jacobs—who had fled slavery saw her freedom purchased by her Northern employer and friend Cornelia Grinnell Willis. A year later, Jacobs was urged to tell her life story, which would provide a woman’s perspective on the full-length freedom narratives written by men like Frederick Douglass. Jacobs’s abolitionist friend Amy Post wrote to Beecher Stowe asking for advice and support for Jacobs’s effort. Instead of responding to Jacobs or Post, Beecher Stowe sent the letter to Willis, asking for verification and permission to use Jacobs’s story in A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which Beecher Stowe was currently writing. A Key was her documentary defense of the picture of slavery in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Jacobs was offended that Beecher Stowe had shared embarrassing details of her experience in slavery with Willis, who had not previously known that part of Jacobs’s history. Jacobs responded to Beecher Stowe that she wanted to tell her own story but would provide her with “some facts for her book.” Beecher Stowe never answered Jacobs’s letters. Was Beecher Stowe just too busy to take on another project? Did she suspect that Jacobs’s account of hiding seven years in an attic was based on Cassy’s stratagem in Chapter XXXIX of Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Even if she did, shouldn’t she have responded directly to Amy Post and Jacobs rather than to Willis? Biographer Joan Hedrick attributes Beecher Stowe’s treatment of Jacobs to “insensitivity bred by class and skin privilege . . . probably exacerbated by her sense of literary ‘ownership ‘ of the tale of the fugitive slave.” Jacobs was right to insist on writing her own story, which she did admirably over the next few years. It took her three more years, until 1861, to find a publisher. Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl powerfully reveals the double oppression faced by enslaved women while providing an inside look at the rich cultural network enslaved people nurtured to keep themselves alive. You can read Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl free online through Project Gutenberg. Please share your comments and questions on any part of Jacobs’s story or this tale of two Harriets. We’d be delighted to hear from you. About the author: Dr. John Getz, Professor Emeritus, Xavier University, retired in 2017 after teaching English there for 45 years. He specializes in American literature, especially nineteenth century, as well as the intersections of literature and peace studies. He has written articles on a variety of authors including Edith Wharton, Sherwood Anderson, and Ursula Le Guin. He appears in the documentary film Becoming Harriet Beecher Stowe, scheduled for release in spring 2020 by Fourth Wall Films. |

Archives

March 2025

Categories

All

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed