Tour Historic Gilbert Avenue

Cincinnati played a large part in the country's abolitionist movement, and coincidently, many 19th century abolitionists lived along the same street, Gilbert Avenue. Although some of these abolitionists lived on Gilbert Avenue at different times, they all had equally huge impacts on Cincinnati and the country as a whole. Gilbert Avenue has seen it all; from the country's first female physician, to the first public discussion on slavery. We invite you to walk along, either virtually or in person, and experience all that Gilbert Avenue has to offer.

Walnut Hills Presbyterian Church

2601 Gilbert Avenue

|

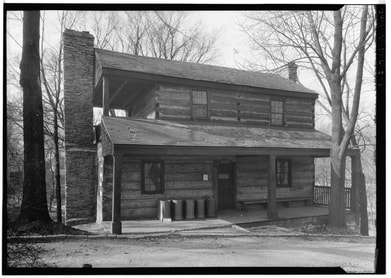

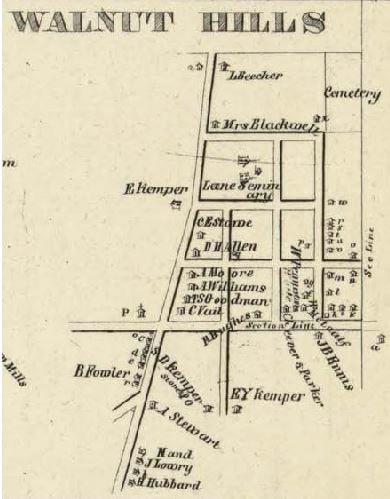

The Kemper Home

In 1791, Reverend James Kemper and his family relocated to Cincinnati and moved to what is now the corner of Kemper Lane and Windsor Street. They bought 150 acres of land from John Cleves Symmes, one of the largest landowners in the Cincinnati area at the time. On their acreage, they established a thriving farmstead, which they named Walnut Hill. Today, the land comprises the majority of the Walnut Hills neighborhood. The Kempers's log home, built in 1804, is one of the oldest still-standing houses built in Cincinnati. Members of the Kemper family lived in the log home until 1897, and in 1912 the house was moved to the Cincinnati Zoo. The log home lived in the Zoo until 1981, when it was relocated by the Ohio Society to its permanent home at the Heritage Village in Sharon Woods. The Kemper’s log home can still be seen there today. The Kempers's Impact on Cincinnati The Kempers's mission for Walnut Hills included promoting faith, freedom, and education. In 1819, Rev. James Kemper helped establish the First Presbyterian Church of Walnut Hills. The remaining tower of the church still exists today at the corner of William Howard Taft and Gilbert Avenue. The Kemper family sold some of their land in 1829 to the Lane brothers, who opened the Lane Theological Seminary. The Seminary would become a center of controversy during the 1834 Lane Debates. The Seminary eventually merged with the Presbyterian Church in 1878. John Kemper’s sons sold off much of their land for development, and as the neighborhood grew, Walnut Hills became one of the most religiously and ethnically diverse neighborhoods of the time. |

Calvin and Harriet Beecher Stowe House

2622 Gilbert Avenue

This home no longer stands.

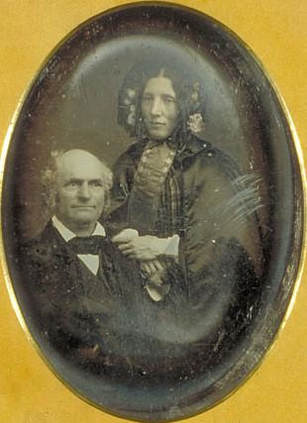

Calvin Stowe and Harriet Beecher Stowe

Calvin Stowe and Harriet Beecher Stowe

Calvin Stowe in Cincinnati

Calvin Stowe moved to Walnut Hills in 1832 when he was appointed as a professor at Lane Seminary. He was married to Eliza Tyler, who became very close friends with Harriet Beecher. Eliza passed away in 1834 and two years later, in January of 1836, Calvin Stowe and Harriet Beecher were married. Although it would have been likely that both Calvin and Harriet lived in the Beecher’s home as newlyweds, they did eventually move to their own home on the Lane Seminary grounds. While the house no longer stands, it is believed to be where the Assumption of The Blessed Virgin Mary Parish resides today.

While in Cincinnati, Calvin Stowe became an important leader in the development of free public schools to integrate new immigrants into American society, especially in the western states. He traveled to England and Europe several times to study education systems. Calvin Stowe also promoted state-supported education and teacher training in the United States.

Although they spent much time apart, Calvin and Harriet’s marriage was an alliance of American social reform and freedom that would change history. While away, Stowe wrote letters to Harriet about the British antislavery movement. Harriet published excerpts of these letters in the Cincinnati Journal. Harriet took on roles as a mother, domestic keeper, and writer, all to support the family while Calvin was working for small wages at the Seminary.

The Stowe Family Moves East

In 1850, Harriet and the children moved from Cincinnati after hard times affected the family. They had little money, and their youngest son, Samuel Charles, was lost to the cholera epidemic of 1849. Calvin accepted another teaching position in Maine, but the struggles followed the Stowe family to the East coast. During a church service, Harriet became inspired to write a story based on her experience with the antislavery movement. Little did she know that this idea would develop into a novel called Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which would become a best seller and catalyst to the Civil War.

Within the first year of its publication, Uncle Tom’s Cabin sold 300,000 copies. It was eventually translated into 75 different languages. Not only did the Stowe’s thrive financially, but Harriet became a household name and leader in the antislavery movement. Uncle Tom’s Cabin became one of the most controversial and influential books in American history.

Calvin Stowe moved to Walnut Hills in 1832 when he was appointed as a professor at Lane Seminary. He was married to Eliza Tyler, who became very close friends with Harriet Beecher. Eliza passed away in 1834 and two years later, in January of 1836, Calvin Stowe and Harriet Beecher were married. Although it would have been likely that both Calvin and Harriet lived in the Beecher’s home as newlyweds, they did eventually move to their own home on the Lane Seminary grounds. While the house no longer stands, it is believed to be where the Assumption of The Blessed Virgin Mary Parish resides today.

While in Cincinnati, Calvin Stowe became an important leader in the development of free public schools to integrate new immigrants into American society, especially in the western states. He traveled to England and Europe several times to study education systems. Calvin Stowe also promoted state-supported education and teacher training in the United States.

Although they spent much time apart, Calvin and Harriet’s marriage was an alliance of American social reform and freedom that would change history. While away, Stowe wrote letters to Harriet about the British antislavery movement. Harriet published excerpts of these letters in the Cincinnati Journal. Harriet took on roles as a mother, domestic keeper, and writer, all to support the family while Calvin was working for small wages at the Seminary.

The Stowe Family Moves East

In 1850, Harriet and the children moved from Cincinnati after hard times affected the family. They had little money, and their youngest son, Samuel Charles, was lost to the cholera epidemic of 1849. Calvin accepted another teaching position in Maine, but the struggles followed the Stowe family to the East coast. During a church service, Harriet became inspired to write a story based on her experience with the antislavery movement. Little did she know that this idea would develop into a novel called Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which would become a best seller and catalyst to the Civil War.

Within the first year of its publication, Uncle Tom’s Cabin sold 300,000 copies. It was eventually translated into 75 different languages. Not only did the Stowe’s thrive financially, but Harriet became a household name and leader in the antislavery movement. Uncle Tom’s Cabin became one of the most controversial and influential books in American history.

Lane Theological Seminary

2820 Gilbert Avenue

Current site of Thompson-MacConnell Cadillac. There is a historical marker located there.

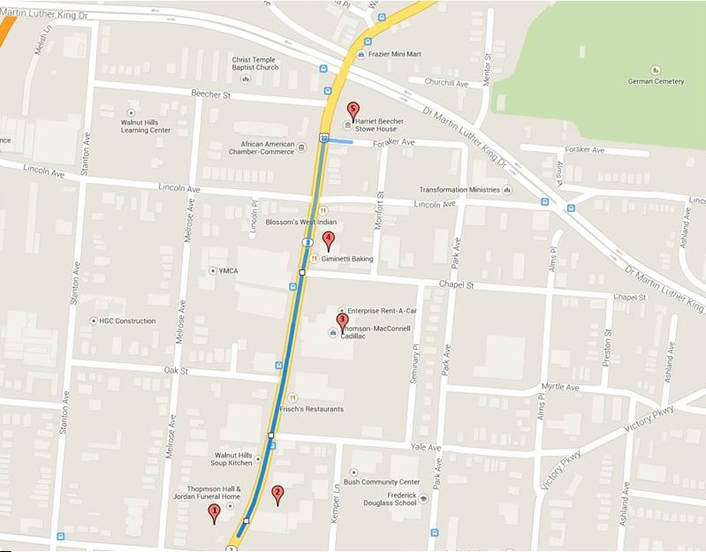

The Lane Theological Seminary

The Lane Theological Seminary

he Lane Theological Seminary Begins

The Lane Theological Seminary was established in 1829 as a school to educate new ministers and spread Presbyterianism in the developing Western states. It was named after two Baptist brothers from New Orleans, Ebenezer and William Lane, who pledged $4,000 for the start of the school. Lyman Beecher was the first president of the Seminary, and through his teachings and social activism efforts, Lane Seminary became a vibrant center for controversial issues.

The Evolution of the Seminary

In 1834, the Lane Seminary held an 18-day-long debate on slavery, which is recognized as the first public discussion on the topic. Issues discussed at the debate included the abolishment of slavery and opposition to American colonization. A radical group of students, led by Theodore Dwight Weld, emerged during these debates and became known as the “Lane Rebels.” Their radical demands for the immediate emancipation of slaves worried Lyman Beecher because they challenged the authority of the school. This conflict led to the departure of the group to Oberlin College, which became an interracial institution dedicated to the emancipation and education of African Americans.

In 1852, Lyman Beecher resigned as president of the seminary and moved back East to be with his son, Reverend Henry Ward Beecher. The seminary struggled financially and was eventually absorbed by the McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago in 1932. The last standing buildings of the seminary were the Westminster Buildings, which were dormitories that were converted into apartments in 1933. By 1956, the seminary was completely demolished, and today the Thomson-MacConnell Cadillac dealership now stands on the old seminary grounds. The stairs that lead up to the seminary can still be seen surrounding the dealership.

The Lane Theological Seminary was established in 1829 as a school to educate new ministers and spread Presbyterianism in the developing Western states. It was named after two Baptist brothers from New Orleans, Ebenezer and William Lane, who pledged $4,000 for the start of the school. Lyman Beecher was the first president of the Seminary, and through his teachings and social activism efforts, Lane Seminary became a vibrant center for controversial issues.

The Evolution of the Seminary

In 1834, the Lane Seminary held an 18-day-long debate on slavery, which is recognized as the first public discussion on the topic. Issues discussed at the debate included the abolishment of slavery and opposition to American colonization. A radical group of students, led by Theodore Dwight Weld, emerged during these debates and became known as the “Lane Rebels.” Their radical demands for the immediate emancipation of slaves worried Lyman Beecher because they challenged the authority of the school. This conflict led to the departure of the group to Oberlin College, which became an interracial institution dedicated to the emancipation and education of African Americans.

In 1852, Lyman Beecher resigned as president of the seminary and moved back East to be with his son, Reverend Henry Ward Beecher. The seminary struggled financially and was eventually absorbed by the McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago in 1932. The last standing buildings of the seminary were the Westminster Buildings, which were dormitories that were converted into apartments in 1933. By 1956, the seminary was completely demolished, and today the Thomson-MacConnell Cadillac dealership now stands on the old seminary grounds. The stairs that lead up to the seminary can still be seen surrounding the dealership.

Elizabeth Blackwell House

2900 Gilbert Avenue

This home no longer stands.

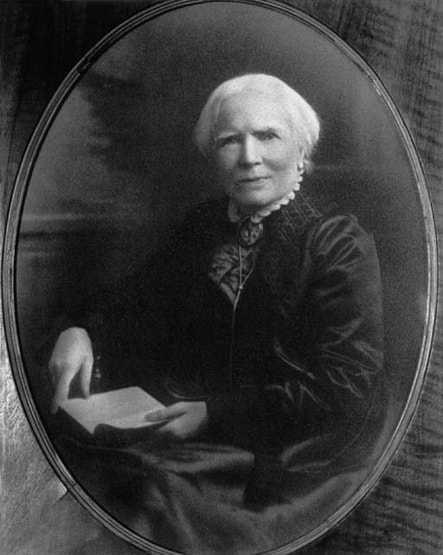

Elizabeth Blackwell M.D. was the first female physician in the United States.

Elizabeth Blackwell M.D. was the first female physician in the United States.

Elizabeth Blackwell Arrives in Cincinnati

In 1838, Elizabeth Blackwell and her family moved to Cincinnati in an attempt to revive a sugar refinery business that had been unsuccessful in New York. Her father, Samuel Blackwell, influenced his children greatly with his liberal and antislavery views. Cincinnati was interesting to the family, not only as one of the centers for the abolition movement, but also as a place to cultivate sugar beets. Sugar beets were an alternative to sugar cane which was produced by slave labor. Unfortunately, Samuel Blackwell passed away three weeks after moving to Cincinnati.

From Teacher to Physician

In an attempt to support the family, the Blackwell sisters opened the Cincinnati English and French Academy for Young Ladies in their own home. In 1844, Elizabeth pursued a teaching job in Henderson, Kentucky, where she was exposed to the shocking realities of slavery in the South. At the end of her teaching contract, she returned to Cincinnati to join her family at their new home in Walnut Hills. While living in Walnut Hills, Elizabeth met Harriet Beecher Stowe and her family, who shared her interest in the abolition movement. She also met Mary Donaldson, a neighbor who was suffering from cancer. Mary was the first person to suggest that Elizabeth become a physician. Elizabeth was initially repulsed by the idea of becoming a doctor, but after teaching in Asheville, North Carolina where she saw the horrible conditions and treatment of slaves, she was convinced to pursue a career in the medical field.

In 1838, Elizabeth Blackwell and her family moved to Cincinnati in an attempt to revive a sugar refinery business that had been unsuccessful in New York. Her father, Samuel Blackwell, influenced his children greatly with his liberal and antislavery views. Cincinnati was interesting to the family, not only as one of the centers for the abolition movement, but also as a place to cultivate sugar beets. Sugar beets were an alternative to sugar cane which was produced by slave labor. Unfortunately, Samuel Blackwell passed away three weeks after moving to Cincinnati.

From Teacher to Physician

In an attempt to support the family, the Blackwell sisters opened the Cincinnati English and French Academy for Young Ladies in their own home. In 1844, Elizabeth pursued a teaching job in Henderson, Kentucky, where she was exposed to the shocking realities of slavery in the South. At the end of her teaching contract, she returned to Cincinnati to join her family at their new home in Walnut Hills. While living in Walnut Hills, Elizabeth met Harriet Beecher Stowe and her family, who shared her interest in the abolition movement. She also met Mary Donaldson, a neighbor who was suffering from cancer. Mary was the first person to suggest that Elizabeth become a physician. Elizabeth was initially repulsed by the idea of becoming a doctor, but after teaching in Asheville, North Carolina where she saw the horrible conditions and treatment of slaves, she was convinced to pursue a career in the medical field.

“I longed to jump up, and taking the chains from those injured, unmanned men, fasten them on their tyrants till they learned . . . the bitterness of [slavery].” Elizabeth Blackwell, as quoted in Barbara A Somervil, Elizabeth Blackwell: America’s First Female Doctor. p. 31.

At the time, pursuing a career as a physician was a difficult task for a woman. Women were believed less capable than men in the male-dominated medical field. While teaching in Asheville, Elizabeth earned enough money to cover the expenses of medical school. She was accepted by Geneva Medical College in New York and influenced the behavior and beliefs of her male classmates. In January of 1849, Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman to graduate with a medical degree in the United States.

Lucy Stone & Henry Blackwell

Lucy Stone, circa 1840–1860

Lucy Stone, circa 1840–1860

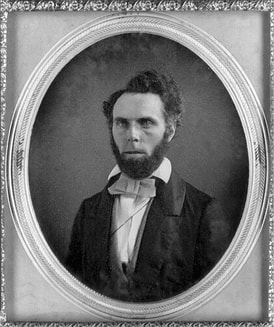

Power Couple Meets in Cincinnati

Lucy Stone first met her future husband, Henry B. Blackwell (brother of Elizabeth Blackwell) in 1849 or 1850 at 18 Main Street in Cincinnati in the hardware store he co-owned (Coombs, Ryland, and Blackwells). Blackwell would later write that on that day, he was so struck with Stone’s “sweet voice, bright smile, pleasant manner and simplicity of dress and character” that he urged his brother Samuel (who later married Antoinette Brown Blackwell) to make her acquaintance.

Although Henry would read about Lucy in the intervening years, they would not meet again until May 1853 at the American Anti-Slavery Society anniversary meeting in New York City. By that time, Lucy had become a prominent woman’s rights and anti-slavery speaker. The following month, Henry saw Lucy speak again in Boston. He began by traveling to Lucy’s family home in West Brookfield, MA, urging her to travel west on a speaking tour he would help arrange. Later that year, Samuel's diary indicates that Lucy stayed with the Blackwell family at their Cincinnati home in Walnut Hills. Even though Lucy declined Henry’s marriage proposals, they continued to court.

Lucy Stone first met her future husband, Henry B. Blackwell (brother of Elizabeth Blackwell) in 1849 or 1850 at 18 Main Street in Cincinnati in the hardware store he co-owned (Coombs, Ryland, and Blackwells). Blackwell would later write that on that day, he was so struck with Stone’s “sweet voice, bright smile, pleasant manner and simplicity of dress and character” that he urged his brother Samuel (who later married Antoinette Brown Blackwell) to make her acquaintance.

Although Henry would read about Lucy in the intervening years, they would not meet again until May 1853 at the American Anti-Slavery Society anniversary meeting in New York City. By that time, Lucy had become a prominent woman’s rights and anti-slavery speaker. The following month, Henry saw Lucy speak again in Boston. He began by traveling to Lucy’s family home in West Brookfield, MA, urging her to travel west on a speaking tour he would help arrange. Later that year, Samuel's diary indicates that Lucy stayed with the Blackwell family at their Cincinnati home in Walnut Hills. Even though Lucy declined Henry’s marriage proposals, they continued to court.

Henry Browne Blackwell (1825–1909) pictured ca. 1845–1860

Henry Browne Blackwell (1825–1909) pictured ca. 1845–1860

A Progressive Partnership

The 1855 marriage of Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell was unconventional, beginning with the ceremony: Lucy retained her surname and did not vow to obey her husband. The couple also authored a widely published “protest” against married women’s legal status. Later that year, both spoke at the National Woman’s Rights convention in Cincinnati.

Throughout their marriage, Stone and Blackwell were collaborators and activists, leading the American Woman Suffrage Association and editing the Woman’s Journal. Their daughter, Alice Stone Blackwell, played an instrumental role in healing the schism between the American Woman Suffrage Association and the National Woman Suffrage Association to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association.

The 1855 marriage of Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell was unconventional, beginning with the ceremony: Lucy retained her surname and did not vow to obey her husband. The couple also authored a widely published “protest” against married women’s legal status. Later that year, both spoke at the National Woman’s Rights convention in Cincinnati.

Throughout their marriage, Stone and Blackwell were collaborators and activists, leading the American Woman Suffrage Association and editing the Woman’s Journal. Their daughter, Alice Stone Blackwell, played an instrumental role in healing the schism between the American Woman Suffrage Association and the National Woman Suffrage Association to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association.

The Harriet Beecher Stowe House

2950 Gilbert Avenue

The Harriet Beecher Stowe House, (as seen c. 2016), still stands. It hosted educators, ministers, and antislavery advocates in the 18 years the Beecher family called Walnut Hills their home.

The Harriet Beecher Stowe House, (as seen c. 2016), still stands. It hosted educators, ministers, and antislavery advocates in the 18 years the Beecher family called Walnut Hills their home.

The Beecher Family in Cincinnati

The Harriet Beecher Stowe House was the official residence of the Lane Seminary president, and Harriet's father - Reverend Lyman Beecher - was the home's first resident.

The Second Great Awakening (a Protestant revival movement during the early nineteenth century) brought Rev. Beecher and his family to Cincinnati to train ministers at the Lane Seminary to “win the West in Protestantism.”

Although Harriet Beecher married Calvin Stowe in 1836 and moved to a nearby property on the Lane Seminary grounds, she frequently visited her father’s home, and gave birth to her first two children in an upstairs bedroom.

The Harriet Beecher Stowe House was the official residence of the Lane Seminary president, and Harriet's father - Reverend Lyman Beecher - was the home's first resident.

The Second Great Awakening (a Protestant revival movement during the early nineteenth century) brought Rev. Beecher and his family to Cincinnati to train ministers at the Lane Seminary to “win the West in Protestantism.”

Although Harriet Beecher married Calvin Stowe in 1836 and moved to a nearby property on the Lane Seminary grounds, she frequently visited her father’s home, and gave birth to her first two children in an upstairs bedroom.

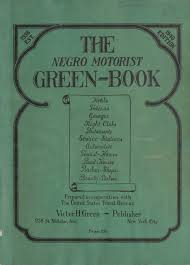

The Harriet Beecher Stowe House becomes the Edgemont Inn

By the 1930s, the Walnut Hills neighborhood was a thriving African American business district. The House itself had become a boarding house and tavern. The Negro Green Motorist Book was developed by Victor Hugo Green in 1936 for African American motorists. Discrimination against African Americans meant that black motorists had trouble finding safe housing, restaurants, rest stops, and other accommodations. The Negro Motorist Green Book listed companies and organization that served and were safe for African Americans. It originally published safe havens in NYC, but then expanded to include all of North America. In the 1940 edition of the Green Motorist Book, the Harriet Beecher Stowe House then referred to as ‘The Edgemont Inn’, was one of only a few taverns listed as safe for African Americans in Cincinnati. Other neighborhood businesses were also included as restaurants, hotels, and beauty parlors.

By the 1930s, the Walnut Hills neighborhood was a thriving African American business district. The House itself had become a boarding house and tavern. The Negro Green Motorist Book was developed by Victor Hugo Green in 1936 for African American motorists. Discrimination against African Americans meant that black motorists had trouble finding safe housing, restaurants, rest stops, and other accommodations. The Negro Motorist Green Book listed companies and organization that served and were safe for African Americans. It originally published safe havens in NYC, but then expanded to include all of North America. In the 1940 edition of the Green Motorist Book, the Harriet Beecher Stowe House then referred to as ‘The Edgemont Inn’, was one of only a few taverns listed as safe for African Americans in Cincinnati. Other neighborhood businesses were also included as restaurants, hotels, and beauty parlors.

|

Web Hosting by iPage