|

In Lyman Beecher’s study, one of the front rooms at the Harriet Beecher Stowe House, one finds two secretary desks, each topped by a bookcase closed with a pair of glass doors. One has a plaque on it saying it was Dr. Beecher’s desk, an unverifiable statement, although we are told it came to the Stowe House from the Lane Seminary, where he was the President for its first 20 years. The books on its shelves are a miscellaneous collection, some Great Books, some not, meant to represent ones that might have been on the shelves in his time. One exception is the two-volume set The Autobiography of Lyman Beecher, edited for Harvard University Press by Barbara Cross. The publisher describes it as “… the colorful self-portrait of a central figure in American Protestantism... The Autobiography is a rich mosaic of records, reminiscences, and correspondence gathered by Beecher’s many children (among them, Harriet Beecher Stowe and Henry Ward Beecher).” The other secretary holds 45 book titles, of which 27 are by members of the Beecher family, while the rest treat them as subject matter. It’s a sampling of the literary output of a family in which nine of the thirteen children became writers, and it calls to mind two famous quips about them. Reverend Leonard Bacon wrote in 1863, the same year Lyman Beecher died, “This country is inhabited by saints, sinners, and Beechers,” and Unitarian minister Theodore Parker called Lyman “the father of more brains than any other man in America.” Those represented by just one title are: Lyman’s Six Sermons on Intemperance (1829); Edward’s The Papal Conspiracy (1855); and Charles’s Harriet Beecher Stowe in Europe (1896). There is one non-Beecher represented, Calvin Stowe, who edited and wrote the introduction to James Barr Walker’s Philosophy of the Plan of Salvation a Book for the Times by an American (1850). Henry Ward has 7 titles to his credit: Evolution & Religion (1855), Norwood: Village Life in New England (1868), Prayers from Plimouth (1887), Lectures to Young Men (1856), Plymouth Collection of Hymns & Tunes (1855), Beecher Sermons (1872), and Star Papers, or Experiences of Art & Nature (1855). Norwood was Henry Ward’s only venture into fiction, as Wikipedia explains: “In 1865, Robert E. Bonner of the New York Ledger offered Beecher twenty-four thousand dollars to follow his sister's example and compose a novel… Beecher stated his intent for Norwood was to present a heroine who is "large of soul, a child of nature, and, although a Christian, yet in childlike sympathy with the truths of God in the natural world, instead of books…” One review of the 549-page tome said, “to read through a novel so very long, so apparently interminable, and so amazingly dull as we are reluctantly constrained to consider Norwood to be, is a real triumph of endurance.” Not surprisingly 17 titles are from Harriet’s pen, including three editions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. As subject Harriet is honored with 13 biographies, far outstripping the two of Henry Ward (Life of Beecher by Abbot & Halliday (1887) and Henry Ward Beecher: An American Portrait by Paxton Hibben (1942), and the one of the entire Beecher family, Milton Rugoff’s The Beechers (1981). One of the titles about Harriet deserves special mention: Harriet: A Play in 3 Acts (1945) by married writing team Florence Ryerson and Colin Clements, which ran for a year on Broadway in 1943. It was dedicated “for Eleanor Roosevelt” and starred Helen Hayes, of whom Time Magazine wrote “But Actress Hayes, acting with her usual skill, aging with her usual art, creates, if not a great and rounded woman, a bustling housewife who is also sore beset.” Finally, there is one title on the shelves that is only distantly related to the Beechers – Herland (1915) by feminist Charlotte Perkins Gilman, which Wikipedia describes as a utopian novel that “describes an isolated society composed entirely of women, who bear children without men (parthenogenesis, a form of asexual reproduction). The result is an ideal social order: free of war, conflict, and domination.” Gilman’s great-grandfather on her father’s side was Dr. Lyman Beecher, and she revered her great-aunt Harriet Beecher Stowe. Four of the nine members in the Beecher party that arrived in Cincinnati in 1832 produced in their lifetimes 90 titles. Wikipedia credits Lyman with 17 published works, daughters Catherine and Harriet with 22 and 34 respectively, and son Henry Ward with 17. Add to that the 26 titles contributed by sons Edward (12) and Charles (14), and it comes to 116 titles! Visitors can find many books by or about Harriet for sale at the HBS House bookstore. Several others described above are in the collection of the Cincinnati and Hamilton County Public Library housed on the second floor. I encourage you to look for them when you come for a tour. About the author:

Frederick Warren is a docent at the Harriet Beecher Stowe House, as well as a tour guide for the Friends of Music Hall. He is a retired estimator for a book printing and binding firm in Cincinnati.

1 Comment

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: July 1, 2021 Media Contact: Christina Hartlieb 513-751-0651 [email protected] (CINCINNATI, OH)– The Harriet Beecher Stowe House is pleased to announce the opening of a brand-new experience for visitors to the historic site in Walnut Hills. “Our Neighborhood Story: A Tour of this Walnut Hills Block,” developed in partnership with Ohio Humanities and the Walnut Hills Historical Society, traces 200 years of the history in one Cincinnati block. This entirely outdoor exhibit is free and open to the public during daylight hours at the historic Harriet Beecher Stowe House, 2950 Gilbert Avenue, Cincinnati OH 45206. Seven panels on the ground of the Harriet Beecher Stowe House (and one panel a few blocks down on Beecher Street at the Walnut Hills Community Garden) explain the significance of the site and the ways that women and men from Walnut Hills developed and sustained the diverse and dynamic neighborhood over the past two centuries. Double-sided outdoor panels feature photographs and illustrations from the neighborhood’s formation in the 1830s around Lane Seminary, through the Civil War and Reconstruction, to a 20th century thriving middle-class neighborhood full of Black-owned businesses, to recent changes brought about by the expansion of MLK Drive and the highway 71 interchange. Visitors are encouraged to think about how people in this neighborhood have use their voices to affect change both locally and around the world how they can use the power of their own voices today. While the Our Neighborhood Story exhibition on the grounds of the Harriet Beecher Stowe House is free, there is a modest fee of $6 for adults/$5 for seniors/$3 for children to tour the house, which holds detailed exhibits explaining how author and abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe's young adult years in Cincinnati led to the landmark publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. For more information on the exhibit or to plan your trip, visit www.stowehousecincy.org or call 513-751-0651. ### ABOUT HARRIET BEECHER STOWE HOUSE The nonprofit Friends of Harriet Beecher Stowe House manages a Cincinnati home where Harriet Beecher Stowe lived during the formative years that led her to write the best-selling novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. This historic site is part of the Ohio History Connection’s network of more than 50 sites and museums across Ohio. For more information about programs and events, call 513-751-0651 or visit www.stowehousecincy.org. Ohio History Connection The Ohio History Connection, formerly the Ohio Historical Society, is a statewide history organization with the mission to spark discovery of Ohio’s stories. As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization chartered in 1885, the Ohio History Connection carries out history services for Ohio and its citizens focused on preserving and sharing the state’s history. This includes housing the state historic preservation office, the official state archives, local history office and managing more than 50 sites and museums across Ohio. For more information on programs and events, visit ohiohistory.org.

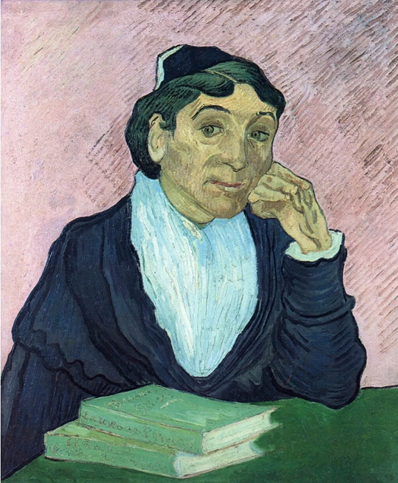

During our recent volunteers Zoom meeting participants were asked to answer 7 multiple choice trivia questions. Only one of these failed to get one correct response from the over 20 folks participating: “Which painter wrote of Harriet that she “helps us to understand how applicable the Gospel is in this day and age,” and later included Uncle Tom's Cabin in a still life? a. Winslow Homer b. Thomas Kinkade c. Georgia O’Keefe d. Vincent Van Gogh” No one chose the correct answer – “d”. I learned of Van Gogh’s admiration for Harriet Beecher Stowe this past July from an article written for a daily email newsletter which I receive, the “Literary Hub.” Entitled “The Writers Vincent van Gogh Loved, From Charles Dickens to Harriet Beecher Stowe: 6 Books Essential to Our Understanding of the Artist,” it was written by Mariella Guzzoni, an independent scholar and art curator living in Bergamo, Italy. Over many years, she has collected editions of the books that Vincent van Gogh read and loved. In March the University of Chicago Press published her study “Vincent's Books: Van Gogh and the Writers Who Inspired Him.” Ms. Guzzoni writes of Van Gogh: “Vincent was an avid and multilingual reader, a man who could not do without books. In his brief life he devoured hundreds of them in four languages, spanning centuries of art and literature. Throughout his life, his reading habits reflected his various personae—art dealer, preacher, painter—and were informed by his desire to learn, discuss, and find his own way to be of service to humanity.” In June 1880 Van Gogh wrote in a letter that he had been reading Beecher Stowe. Ms. Guzzoni writes: “Vincent, 27, is in the mining region of the Borinage, in Belgium. For a year and a half he has been among the miners, seeking to console the workers of the underworld. He is at a dead end. He cuts himself off from the world, and immerses himself in reading. Two books were crucial in what was to become the period of his rebirth as an artist: Histoire de la révolution française (History of the French Revolution, in 9 volumes), by the greatest of the French romantic historians, Jules Michelet, and Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe, the novel that helped foment anti-slavery sentiment in the United States and abroad. Michelet’s new approach to writing history dared to give the People agency, placing them firmly at the center of the revolutionary dynamic. Vincent, too, would put the faces of the People at the center of his revolution in portraiture. Michelet himself described Beecher Stowe as “the woman who wrote the greatest success of the time, translated into every language and read around the world, having become the Gospel of liberty for a race.” What are the common themes? The fight for freedom and independence; the moral importance of literature; the plight of the poor and deprived. Both books were modern gospels for Vincent in a moment of great doubt, when he rejected the “established religious system.” “Take Michelet and Beecher Stowe, they don’t say, the gospel is no longer valid, but they help us to understand how applicable is it in this day and age, in this life of ours, for you, for instance, and for me…” In Van Gogh’s painting “L'Arlésienne (portrait of Madame Ginoux),” of which there are more than one version, there are two books on the table. One is Dickens' Christmas Tales and the other Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin. About the author:

Frederick Warren is a docent at the Harriet Beecher Stowe House, as well as a tour guide for the Friends of Music Hall. He is a retired estimator for a book printing and binding firm in Cincinnati. Stay tuned for additional posts answering questions posed by the participants of the Harriet Beecher Stowe House Community Connection Facebook group. CLICK HERE to join the group and submit your own questions to our volunteer team! Today's question is answered by docent and board member Frederick Warren. Question: How did Harriet Beecher Stowe learn to write a novel?

Growing up in Litchfield, Connecticut, Harriet became an avid reader. As the child of a Congregational minister she was steeped in the Bible. Though her father Lyman’s faith frowned on fiction, the Beecher family was introduced to Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe and to Lord Byron’s poetry by Harriet’s uncle Samuel Foote, a sea captain fluent in French and Spanish, and the ban on novels was lifted. Harriet remembered discovering her father Lyman’s copy of Arabian Nights and being “transported to foreign lands.” Litchfield was a cultural center, boasting the first stand-alone law school in the U.S. and the country’s first important early school for women, Sarah Pierce’s Female Academy. Harriet entered there at the age of eight, four years earlier than the normal starting age. There she read classics of English literature from Milton, Dryden, and Fielding. She began writing weekly compositions at the age of nine, leading her father to observe that “Harriet is a great genius…She is as odd as she is intelligent and studious…” Just as important as her schooling in Harriet’s learning to write were the domestic literary efforts within the Beecher family. People entertained themselves with readings of essays and poems, and Harriet remembered her eldest sister Catharine often writing for the family. People also wrote letters, a skill that was taught at school, and they were often read aloud in the parlor. And formal literary clubs that met in people’s homes were popular. Harriet honed her powers of observation of character and her story-telling ability in this fashion. She then completed her formal education at Catharine’s academy for women in Hartford, where she began her journalism career by editing issues of the school newspaper. Harriet served her literary apprenticeship in Cincinnati, beginning in 1833 by writing a Primary Geography for Children for Catharine’s Western Female Institute in downtown Cincinnati. The book’s success, due to its personal voice and evocative descriptions, led to her invitation to join the Semi-Colon Club, a literary society that was sponsored by the very same uncle Samuel Foote who has so influenced her as a child. The members would contribute stories, essays, and sketches. Soon Harriet’s character sketch “Uncle Lot” had won the Western Monthly Magazine’s prize competition and was the first of many to be published. By 1843 she had published her first collection of such pieces, The Mayflower: Or, Sketches of Scenes and Characters Among the Descendants of the Pilgrims. She was well on the way to finding her literary voice that we know from Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Note: The source material for this brief essay is Harriet Beecher Stowe: A Life by Joan Hedrick (Oxford University Press 1994) and Crusader in Crinoline: the Life of Harriet Beecher Stowe by Forrest Wilson (J. B. Lippincott 1941). About the author: Frederick Warren is a docent at the Harriet Beecher Stowe House, as well as a tour guide for the Friends of Music Hall. He is a retired estimator for a book printing and binding firm in Cincinnati. |

Archives

March 2025

Categories

All

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed