Harriet credited her father with teaching her the evil of slavery when she was 10 years old, at the time of the national debate over the Missouri Compromise, which admitted Missouri to the Union as a slave state and Maine as a free state. She wrote “…one of the strongest & deepest impressions on my mind were my father’s sermons & prayers…his prayers night & morning in the family for ‘poor oppressed bleeding Africa’ that the time for her deliverance in the family might come…which indelibly impressed my heart…” She ascribes the fact that “every brother I have has been in his sphere a leading anti slavery man” to this upbringing.

At the conclusion of the letter to Douglass Harriet speaks of the mission she was undertaking with the writing of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, her method of preaching against slavery by her story that showed that the enslaved were true Christians: “This movement must and will become a purely religious one…christians north and south will give up all connection with & take up their testimony against it…” Clearly the seeds of her writing her anti-slavery novel were sown in her childhood. About the author:

Frederick Warren is a docent at the Harriet Beecher Stowe House, as well as a tour guide for the Friends of Music Hall. He is a retired estimator for a book printing and binding firm in Cincinnati.

0 Comments

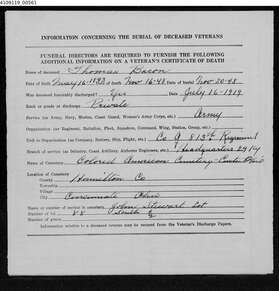

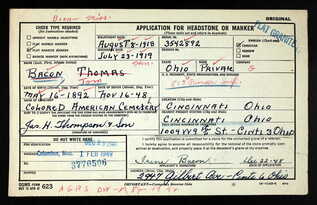

1930s image of 2950 Gilbert Avenue as the Edgemont Inn, a boarding house. 1930s image of 2950 Gilbert Avenue as the Edgemont Inn, a boarding house. Today we honor WWI Veteran Tom Bacon – a resident of the Edgemont Inn Boarding House. During the 1930s and early 1940s, the House now called the Harriet Beecher Stowe House was a long-term boarding house for African Americans and a tavern, called the Edgemont Inn, listed in the Green Motorist Book. The same home that the Beecher family called home in the 1830s and 1840s continued to be a welcoming place for African Americans a century later. Clearly, buildings change over time. A 188-year-old structure cannot be expected to serve the same purpose and the same individuals for its entire existence.  Burial document for Tom Bacon Burial document for Tom Bacon Since we have the census records from 1940, we have been able to start the process of learning more about the lives of those inhabitants. Tom Bacon was one resident. He also served his country during the First World War and was stationed in France on Armistice Day, November 11, 1918. Tom was born in 1892 in Mississippi. After his military service, he ended up in Cincinnati during the Great Depression.  Application for veteran's headstone Application for veteran's headstone Using primary source records collected by a volunteer, I set out to find Tom’s last resting place. We know that he passed away in November 1948 from pneumococcal meningitis and at that point, he lived in a house across the street at 2947 Gilbert Avenue. He was buried in the American Colored Cemetery, located on Duck Creek near Kennedy Avenue. (It is now known as the United American Cemetery). Finding his gravesite was not exactly easy though.  During quarantine earlier this year, my family and I set out to find Tom Bacon’s grave. On a Saturday in April, my teenage son and I ventured to the cemetery. Armed with a plot number and map, we thought it would be an easy task. When we got there, though, we discovered that the road was in poor condition, many of the smaller headstones were either overgrown or dislocated, and there were no section markings. We had no luck when we searched in the back loop where we thought it would be located. Connor and I decided to regroup.  The following weekend, my husband Eric did some additional research on where WWI soldiers were concentrated in the cemetery. The section numbering system may have changed over time because our new estimate was on the opposite side of the cemetery. The two of us embarked on another try. This time we searched an area close to the front entrance. We discovered several WWI and WWII headstones located in that section and after a little perseverance, we found Tom Bacon’s. We were able to document its location. The Harriet Beecher Stowe House plans to continue research and illustration of the lives and stories of the occupants of the House over the past 188 years. We are working on several partnerships that will help in this endeavor. Today we honor Tom Bacon and thank him for his service to the United States and for “making the world safe for democracy.” Author: Christina Hartlieb is Executive Director of the Harriet Beecher Stowe House.

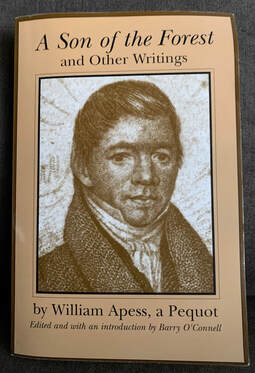

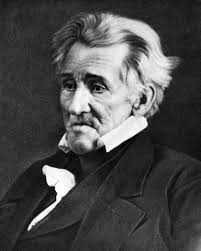

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: November 6, 2020 Media Contact: Christina Hartlieb 513-751-0651 [email protected] 20th century porch and paint coming off to restore 1840s appearance (CINCINNATI, OH)– Site restoration is active at the Harriet Beecher Stowe House in Walnut Hills, a site of the Ohio History Connection. In the past few weeks, historic restoration experts have removed decorative wooden brackets that were added to “Victorianize” the house in the late 1800s and they have detached the large front porch that was added in the 20th century. Many of these elements are being saved and stored for future museum exhibits. Up to 17 layers of paint are currently being removed through chemical and manual processes, with special attention being paid to safe disposal of all potentially hazardous elements. The paint removal will make way for masonry repair, tuckpointing, and repainting in historically-accurate colors determined through historic paint analysis last summer. This research determined the color of the home at the time the Beechers occupied it in the 1840s was a shade of yellow with dark green shutters. The house remains OPEN to tours by appointment during this restoration project and is also continuing its regular programming schedule online. Built in 1832, the Harriet Beecher Stowe House was originally the president’s home on the campus of Lane Theological Seminary. It is the final property remaining from the campus in Walnut Hills. Harriet Beecher Stowe, who moved to Cincinnati with her father at the age of 21, lived in Cincinnati for 18 years and went on to write the influential anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published in 1852. This historic site is located at 2950 Gilbert Avenue in Cincinnati. The Beecher family lived in the home from 1832-1851, including Harriet’s older sister Catherine Beecher, a national leader in teacher training for women and younger sister Isabella Beecher who would go on to be influential in the women’s suffrage movement in Connecticut. The house was subsequently occupied by three generations of the Monfort family who made significant additions and renovations to the home. In the 20th century the site served as a long-term boarding house and had a tavern that was listed in the Green Book. The house was purchased in 1943 by the Harriet Beecher Stowe Home Memorial Association and opened to the public as a historic site in 1949. The site’s last major renovation project took place in the 1970s under the leadership of George Wilson and the Citizen’s Committee on Youth. The Harriet Beecher Stowe House is an Ohio History Connection historic site and is managed locally by the Friends of Harriet Beecher Stowe House. For more information on the site, visit www.stowehousecincy.org or call 513-751-0651. ### ABOUT HARRIET BEECHER STOWE HOUSE The nonprofit Friends of Harriet Beecher Stowe House manages a Cincinnati home where Harriet Beecher Stowe lived during the formative years that led her to write the best-selling novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. This historic site is part of the Ohio History Connection’s network of more than 50 sites and museums across Ohio. For more information about programs and events, call 513-751-0651 or visit www.stowehousecincy.org. Ohio History Connection The Ohio History Connection, formerly the Ohio Historical Society, is a statewide history organization with the mission to spark discovery of Ohio’s stories. As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization chartered in 1885, the Ohio History Connection carries out history services for Ohio and its citizens focused on preserving and sharing the state’s history. This includes housing the state historic preservation office, the official state archives, local history office and managing more than 50 sites and museums across Ohio. For more information on programs and events, visit ohiohistory.org.  A Son of the Forest and “An Indian’s Looking-Glass for the White Man” In 1829, Harriet Beecher, though still in her teens, was a teacher at her sister Catherine’s Hartford Female Seminary. She was also an enthusiastic participant in the school’s campaign of writing letters, petitions, and circulars on behalf of the Cherokee Indians. In President Andrew Jackson’s State of the Union address in 1829, he supported calls for the Cherokees’ forced relocation from their ancestral homeland in Georgia to federal territory west of the Mississippi. Harriet decried that policy. That same year, William Apess’s A Son of the Forest became the first extensive autobiography written and published by a Native American. With Native American, white, and possibly African American ancestry, Apess identified with the remnant of the Pequot people, a group his father had joined. Most Pequots had been massacred or dispersed by whites in the Pequot War of the 1630s. Son of the Forest traces Apess’s struggle with alcoholism, military service for the U.S. in the War of 1812, and conversion to evangelical Methodism. He became an ordained minister in the newly forming Protestant Methodist Church. In Apess’s autobiography and other works such as “An Indian’s Looking-Glass for the White Man” (1833), Christianity serves as a standard by which to judge—and condemn—white treatment of Native Americans. (Apess preferred the term “Natives” to the more common “Indians,” which he considered “a slur upon an oppressed and scattered nation.”) One of Apess’s important strategies was to link the oppression of Native Americans with that of African Americans and other people of color around the world: “If black or red skin or any other skin of color is disgraceful to God, it appears he has disgraced himself a great deal—for he has made fifteen colored people to one white and placed them here upon this earth.” In addition to his writing, Apess became an activist for the rights of the Mashpee people in Massachusetts. He was jailed for civil disobedience, and the Mashpees’ nonviolent protest won some of their demands. Apess died in 1839 at the age of 41. We don’t know if Harriet read his work, but scholars think that Apess may have influenced Thoreau, Melville, and especially Frederick Douglass as he was writing “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?”. You can read Son of the Forest and “An Indian’s Looking-Glass for the White Man” on line for free. Just search by title. Let us know what connections you see between Apess’s work and Douglass’s “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?”. Or what about connections to writing from our own time? About the author:

Dr. John Getz, Professor Emeritus, Xavier University, retired in 2017 after teaching English there for 45 years. He specializes in American literature, especially nineteenth century, as well as the intersections of literature and peace studies. He has written articles on a variety of authors including Edith Wharton, Sherwood Anderson, and Ursula Le Guin. He appears in the documentary film Becoming Harriet Beecher Stowe, scheduled for release soon by Fourth Wall Films.  Elk Lick House, home of Senator Thomas Morris at Heritage Village Museum in Sharonville, OH Elk Lick House, home of Senator Thomas Morris at Heritage Village Museum in Sharonville, OH Ohio is full of fascinating stories of courage and conviction--and many of them are connected to each other. Many thanks to Steve Preston from Heritage Village Museum for sharing about Senator Thomas Morris, a US Senator who represented Ohio during the early years the Beechers lived in Cincinnati. Morris also ran for President on a ticket with Cincinnati abolitionist newspaper editor James Birney, whose work and activism influenced Harriet Beecher Stowe on her path to becoming an abolitionist author.  Senator Thomas Morris Senator Thomas Morris Thomas Morris is a forgotten titan of Ohio politics. Serving only one term as a United States Senator from Ohio, 1833-1839, Morris left his mark on national politics because of slavery. Voted in on the coattails of the Jackson presidency, Morris stood strong with the president on the issues of the banking system and ‘nullification.” As time went on, he became an early opponent of slavery; this put him at odds with the Jacksonian Machine that got him elected. Born in Berks County, Pennsylvania, January 3, 1776, Morris was the fifth child of a Baptist minister and his wife. They soon moved to Clarksburg, Virginia, now West Virginia. Tradition holds that his anti-slavery beliefs were a result of his mother’s views. His mother, Ruth, was the daughter of a Virginia planter. Seeing the hardships of her father’s slaves had an impact on her to the point of not accepting four slaves as part of her inheritance. It should be noted, however, that she also did not free them. If indeed this was where the seeds were sown for his anti-slavery beliefs, they would not surface until his time as a United States Senator.  President Andrew Jackson President Andrew Jackson After a brief stint, searching for Indians in the back country, as a Wood Ranger, under the command of Captain Levi Morgan, Thomas Morris arrived at the Columbia settlement in 1795. He worked as a store clerk for several years, married Rachel Davis in 1797, then moved to Bethel, Ohio in Clermont County in 1800. He studied for and passed the bar to become a lawyer in 1804. He set up shop in Bethel and soon had a successful practice as a frontier lawyer. Thanks to his success, he rose to prominence and was elected to the Ohio House of Representatives in 1806. He went on to serve in the Ohio Senate as well before gaining the national stage as United States Senator from Ohio 1833-1839. His selection by the Democrats for the senate seat was largely viewed as reward for his ardent support of the re-election of Andrew Jackson. Morris proved his loyalty by supporting Jackson’s war with the National Bank and introducing anti-nullification legislature that passed through the government. This may have been the high-water mark for this relationship.  Senator John C. Calhoun Senator John C. Calhoun As the issue of slavery raised its ugly head due to America’s expansion, legislators began to take sides based on state location and personal beliefs. On January 7, 1836, Senator Morris introduced an anti-slavery bill in the 24th Congress, which raised the ire of South Carolina’s John C. Calhoun. In response to Calhoun’s attack, Morris stood his ground and seemingly broke what was a “gentleman’s agreement” not to broach the subject at length.  James G. Birney James G. Birney The gauntlet had been thrown down and Morris was now hailed a torch bearer by abolitionists such as Cincinnati’s James G. Birney. While popular in those circles, his views were not so within the party that elected him. President Andrew Jackson went so far as to “shun” him on his visit to Cincinnati. The writing was on the wall; Morris had lost the support of his party due to his outspoken views on slavery. As the Senator’s first term came to a close, he did not seek a second term in the senate. Thomas Morris returned to Clermont County. In 1840, he began to work at the Elk Lick Mill property owned in partnership by Charles White, his son-in-law, and others. The property had a sawmill, gristmill, and distillery on site. Morris split his time between his home in Bethel and working and staying on the grounds of the Elk Lick House compound. It appears that apart from running for vice-president on the Liberty Party ticket with James Birney in 1844, most of Morris’ time was spent at Elk Lick Mills. So much so that three mortgages were owed to Thomas Morris’ estate after his death December 7, 1844.  Elk Lick House at Heritage Village Elk Lick House at Heritage Village A rise in the value of the Elk Lick property indicates that the Elk Lick House front addition was probably built while Morris was still alive, perhaps as his retirement home. To reinforce this possibility, the census of 1850, according to researcher, Mary Laudrick, shows Charles White, Thomas Morris’ widow and three daughters all living at Elk Lick House. Regardless, Senator Morris left his mark on the anti-slavery movement, Clermont County, and Elk Lick House. Elk Lick house was purchased by the Miami Purchase Association, now Historical Southwest Ohio, in 1969 to save it from being destroyed when the Army Corp of Engineers flooded the Elk Lick Valley to create East Fork Lake. The beautiful carpenter gothic style Elk Lick House is now part of Heritage Village Museum located inside Sharon Woods Park in Sharonville, Ohio. About the author: Steve Preston has been Education Director at Heritage Village Museum in Sharonville, OH since 2012. He is responsible for creating quality educational programming and uses his historical research to bring historical figures to life through first-person interpretation. He holds bachelor’s degrees in history and education from Manchester College and a master’s degree in public history from Northern Kentucky University. He is a frequent contributing columnist to the Northern Kentucky Tribune’s “Our Rich History” section. When he’s not sharing his love of history, he’s playing catch with his son or taking in a Cincinnati Reds game. He also enjoys music and taking trips with his family. About Heritage Village Museum:

Heritage Village Museum is open for outside only self-guided tours Wed. – Fri.: 10 a.m. – 4 p.m. Adults: $2, Children 5-11 $1, Children under 4 and members are free. Visitors will receive a booklet with information about the buildings in the Village. Face masks are suggested. Heritage Village Museum and Educational Center is located inside Sharon Woods Park, behind Sharon Center at 11450 Lebanon Rd. Sharonville, Ohio 45241. A Great Parks of Hamilton County parking permit may be required. Heritage Village Museum also has events throughout the year. Visit HeritageVillageCincinnati.org to learn more.  “Harriet Beecher Stowe in Florida, 1867-1884” by Olav Thulesius (2001) This short (170 pages) work answers the questions: Why did Harriet go to Florida, why did she settle in Mandarin, and how was she received? The book’s great virtue, as the author says, is that he “let the writer of Palmetto Leaves speak for herself, painting a picture of Florida….” In the preface the author writes that he became interested in the subject while writing his “Edison in Florida” (1997). In addition to exploring Harriet’s role as “Florida’s most eminent promoter,” Thulesius shows “that she also sounded an early voice for the protection of the environment.” The book begins with brief background material on both the state of Florida and the life of Harriet, with a special emphasis on her health issues and her attraction to hydropathy, or the water-cure movement. Florida attracted Harriet not only for its reputation for healing, but also as an escape or refuge from the pressures of her fame, the turmoil of her brother Henry’s adultery trial, and cost of keeping up Oakholm, her impractical Hartford mansion. We learn of her first foray to Florida, the less-than-successful attempt to set-up her son Frederic with the Laurel Grove cotton plantation. The story moves on to her falling in love with the area known as Mandarin for its orange cultivation, and her purchase of a cabin along the St. Johns river. The author investigates Harriet’s project of establishing a school to educate formerly enslaved persons, and its connection to an earlier pledge she had made to Frederick Douglass. After chapters about Harriet’s house, and the school and the church that she helped establish, we learn how her collection of writings about Florida, Palmetto Leaves, came to be published. The book includes reports of Harriet’s explorations in Florida, providing a view of her love of animals and of nature. Harriet recruited her brother Charles to move to Florida, and the author details his role as plantation owner, clergyman, and Florida’s second Superintendent of public instruction. In her later years Harriet was forced to give up her Southern idyll, first because of her husband Calvin’s health and later her own infirmities. The book concludes with the story of the only trace that remains in Mandarin, a Tiffany window in the church, which sadly was destroyed in 1964 by Hurricane Dora. Thulesius’s writing is sometimes less than lyrical but always concise and informative, and there are many helpful illustrations. It is a rewarding read. About the author:

Frederick Warren is a docent at the Harriet Beecher Stowe House, as well as a tour guide for the Friends of Music Hall. He is a retired estimator for a book printing and binding firm in Cincinnati. |

Archives

March 2025

Categories

All

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed