|

This post continues a series discussing some of the United States's pressing political issues leading up to the Civil War, when the impact of Harriet Beecher Stowe's writing was also being felt across the country. This installment discusses the abolitionist work of Henry Ward Beecher, Harriet's younger brother who had studied at Lane Seminary in Cincinnati and pastored in Indianapolis before moving to New York. CLICK HERE to read previous installments. The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 called for popular sovereignty, whether the Kansas Territory would allow or prohibit slavery, and thus enter the Union as a slave state or a free state would be left up to the people living there. Both pro- and anti-slavery supporters tried to lure settlers to Kansas in order to sway their decision one way or the other. Missouri entered the Union as a slave state in 1821 and many of its citizens held pro-slavery views. Some of them crossed into Kansas claiming to be residents in an attempt to influence the decision. The seven year conflict was characterized by electoral fraud, raids, and murders carried out in Kansas and neighboring Missouri by pro-slavery "Border Ruffians" and anti-slavery "Free-Staters." The antagonism between sides verged on civil war, and the period became known as "Bleeding Kansas.”  Henry Ward Beecher Henry Ward Beecher Henry Ward Beecher was preacher and passionate abolitionist. His Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, NY, along with the New England Immigrant Aid Society, founded in Boston, raised money to send rifles to help the anti-slavery settlers protect themselves from the Border Ruffians. These became known as Beecher’s Bibles after Henry Ward stated that trying to teach slave owners the errors of their ways was like reading “the Bible to Buffaloes.” On March 30, 1855, the Kansas Territory elected its first territorial legislature who would decide whether the territory would allow slavery. Border Ruffians from Missouri again streamed into the territory to vote, and pro-slavery delegates were elected to 37 of the 39 seats. Questions about electoral fraud resulted in a subsequent special election in May but the pro-slavery camp again prevailed with an 29–10 advantage. Congress sent a three-man special committee to the Kansas Territory in 1856 in response to the disputed votes and rising tension, The committee report concluded that had the March election been limited to "actual settlers" it would have elected a “free-state” legislature. The report also stated that the legislature actually seated "was an illegally constituted body, and had no power to pass valid laws”. Nevertheless, the pro-slavery legislature residing in Shawnee Mission, Kansas, began passing laws favorable to slaveholders. In August, anti-slavery residents met to formally reject the pro-slavery laws passed by what they called the "Bogus Legislature". They quickly elected their own Free-State delegates to a separate legislature based in Topeka and drafted the first territorial constitution, the Topeka Constitution. The federal government under the administration of President Franklin Pierce refused to recognize the Free-State legislature. In a message to Congress on January 24, 1856, Pierce declared the Topeka government insurrectionist in its stand against pro-slavery territorial officials. These “rival” constitutions were the first of several written by pro and anti slavery legislators who considered the opponent’s constitutions illegitimate. Violent conflict across eastern Kansas lasted for several years most notably the sacking of Lawrence Kansas and the presence of a strident abolitionist named John Brown. The hostilities continued until a new territorial governor, John W. Geary, took office and managed to prevail upon both sides for peace. Ultimately, Kansas was admitted to the Union as a free state in January, 1861, following the departure of Southern legislators from Congress during the secession crisis. Throughout the Civil War Union control of Kansas was never seriously threatened. Sources: The War Before the War by Andrew Delbanco (2018) Penguin Press https://www.kshs.org/kansapedia/kansas-territory/14701 About the author:

Dr. Nicholas Andreadis is a volunteer at the Harriet Beecher Stowe House. He was a professor and dean at Western Michigan University prior to moving to Cincinnati.

1 Comment

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

January 15, 2021 Media Contact: Christina Hartlieb 513-751-0651 [email protected] The Harriet Beecher Stowe House is closed to the public effective Friday, January 15, 2021 due to Hamilton County’s Level 4 (purple) classification. As a site of the Ohio History Connection, we follow their direction regarding public visitor safety for the site system. According to their coronavirus policy, sites will be closed to the public in all counties receiving a Level 4 (purple) rating from the Ohio Department of Health Public Health Advisory System. We will re-open to the public at the direction of the Ohio History Connection. Any visitors with previously scheduled tours will be contacted regarding their appointments. Staff will continue regular employment from home or on-site according to the nature of their work. See updates at www.stowehousecincy.org. Online programming at the Harriet Beecher Stowe House will continue as previously scheduled during the public closure. February programs include:

### About Harriet Beecher Stowe House The nonprofit Friends of Harriet Beecher Stowe House manages a Cincinnati home where Harriet Beecher Stowe lived during the formative years that led her to write the best-selling novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. This historic site is part of the Ohio History Connection’s network of more than 50 sites and museums across Ohio. For more information about programs and events, call 513-751-0651 or visit www.stowehousecincy.org. Ohio History Connection The Ohio History Connection, formerly the Ohio Historical Society, is a statewide history organization with the mission to spark discovery of Ohio’s stories. As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization chartered in 1885, the Ohio History Connection carries out history services for Ohio and its citizens focused on preserving and sharing the state’s history. This includes housing the state historic preservation office, the official state archives, local history office and managing more than 50 sites and museums across Ohio. For more information on programs and events, visit ohiohistory.org. Two landmark cultural centers on either side of The Ohio work to add meaning and relevance to their offerings.

Harriet Beecher Stowe House The big white house at the corner of Gilbert and MLK in Walnut Hills looks dramatically different right now, and a little less white. Restoration crews have been working steadily for several months uncovering the original style and architecture of the Harriet Beecher Stowe House. The house’s original Federal architectural style is now clear to see. Keep reading at moversmakers.org. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

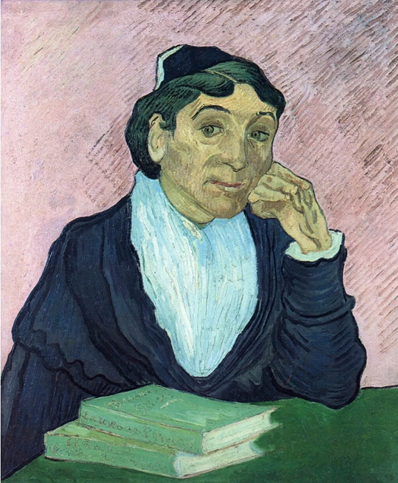

December 22, 2020 Media Contact: Christina Hartlieb 513-751-0651 [email protected] Watching Time Roll Back at the Harriet Beecher Stowe House House’s original architecture uncovered as porch, paint, and bay windows are removed (CINCINNATI, OH)– The big white house at the corner of Gilbert and MLK in Walnut Hills looks dramatically different right now. Restoration crews have been working steadily for several months uncovering the original style and architecture of the Harriet Beecher Stowe House. The house’s original Federal architectural style is now clear to see. Up to 17 layers of paint have been removed from the brick home, revealing infinite details about how the house was constructed in 1832 when it was built as the president’s home for Lane Theological Seminary. The house’s memorable large front porch, which was added in the early 20th century has also been removed, uncovering outlines of the smaller portico from the mid 19th century. Restoration crews also removed large bay windows on both the first and second floors of the home, taking the house’s footprint back to the early 1800s. According to Executive Director Christina Hartlieb, this restoration is daily revealing fascinating new information about how the house was put together and how various members of the Beecher family may have used the rooms during their nearly twenty-year residence in Cincinnati. Revealing the original façade helps the site’s visitors get an immediate sense of the Beecher’s time period in ways that had been more difficult when the history was hidden under decades of new additions. The Harriet Beecher Stowe House remains OPEN to tours by appointment during this restoration project. 2021 book clubs, discussion groups and lectures will begin online in February. Built in 1832, the Harriet Beecher Stowe House was originally the president’s home on the campus of Lane Theological Seminary. It is the final property remaining from the campus in Walnut Hills. Harriet Beecher Stowe, who moved to Cincinnati with her father at the age of 21, lived in Cincinnati for 18 years and went on to write the influential anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published in 1852. During the 1930s-1940s the house served as an African American boarding house and tavern listed in the Green Motorist Book. This historic site is located at 2950 Gilbert Avenue in Cincinnati. The Harriet Beecher Stowe House is an Ohio History Connection historic site and is managed locally by the Friends of Harriet Beecher Stowe House. For more information on the site, visit www.stowehousecincy.org or call 513-751-0651. ### ABOUT HARRIET BEECHER STOWE HOUSE The nonprofit Friends of Harriet Beecher Stowe House manages a Cincinnati home where Harriet Beecher Stowe lived during the formative years that led her to write the best-selling novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. This historic site is part of the Ohio History Connection’s network of more than 50 sites and museums across Ohio. For more information about programs and events, call 513-751-0651 or visit www.stowehousecincy.org. Ohio History Connection The Ohio History Connection, formerly the Ohio Historical Society, is a statewide history organization with the mission to spark discovery of Ohio’s stories. As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization chartered in 1885, the Ohio History Connection carries out history services for Ohio and its citizens focused on preserving and sharing the state’s history. This includes housing the state historic preservation office, the official state archives, local history office and managing more than 50 sites and museums across Ohio. For more information on programs and events, visit ohiohistory.org During our recent volunteers Zoom meeting participants were asked to answer 7 multiple choice trivia questions. Only one of these failed to get one correct response from the over 20 folks participating: “Which painter wrote of Harriet that she “helps us to understand how applicable the Gospel is in this day and age,” and later included Uncle Tom's Cabin in a still life? a. Winslow Homer b. Thomas Kinkade c. Georgia O’Keefe d. Vincent Van Gogh” No one chose the correct answer – “d”. I learned of Van Gogh’s admiration for Harriet Beecher Stowe this past July from an article written for a daily email newsletter which I receive, the “Literary Hub.” Entitled “The Writers Vincent van Gogh Loved, From Charles Dickens to Harriet Beecher Stowe: 6 Books Essential to Our Understanding of the Artist,” it was written by Mariella Guzzoni, an independent scholar and art curator living in Bergamo, Italy. Over many years, she has collected editions of the books that Vincent van Gogh read and loved. In March the University of Chicago Press published her study “Vincent's Books: Van Gogh and the Writers Who Inspired Him.” Ms. Guzzoni writes of Van Gogh: “Vincent was an avid and multilingual reader, a man who could not do without books. In his brief life he devoured hundreds of them in four languages, spanning centuries of art and literature. Throughout his life, his reading habits reflected his various personae—art dealer, preacher, painter—and were informed by his desire to learn, discuss, and find his own way to be of service to humanity.” In June 1880 Van Gogh wrote in a letter that he had been reading Beecher Stowe. Ms. Guzzoni writes: “Vincent, 27, is in the mining region of the Borinage, in Belgium. For a year and a half he has been among the miners, seeking to console the workers of the underworld. He is at a dead end. He cuts himself off from the world, and immerses himself in reading. Two books were crucial in what was to become the period of his rebirth as an artist: Histoire de la révolution française (History of the French Revolution, in 9 volumes), by the greatest of the French romantic historians, Jules Michelet, and Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe, the novel that helped foment anti-slavery sentiment in the United States and abroad. Michelet’s new approach to writing history dared to give the People agency, placing them firmly at the center of the revolutionary dynamic. Vincent, too, would put the faces of the People at the center of his revolution in portraiture. Michelet himself described Beecher Stowe as “the woman who wrote the greatest success of the time, translated into every language and read around the world, having become the Gospel of liberty for a race.” What are the common themes? The fight for freedom and independence; the moral importance of literature; the plight of the poor and deprived. Both books were modern gospels for Vincent in a moment of great doubt, when he rejected the “established religious system.” “Take Michelet and Beecher Stowe, they don’t say, the gospel is no longer valid, but they help us to understand how applicable is it in this day and age, in this life of ours, for you, for instance, and for me…” In Van Gogh’s painting “L'Arlésienne (portrait of Madame Ginoux),” of which there are more than one version, there are two books on the table. One is Dickens' Christmas Tales and the other Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin. About the author:

Frederick Warren is a docent at the Harriet Beecher Stowe House, as well as a tour guide for the Friends of Music Hall. He is a retired estimator for a book printing and binding firm in Cincinnati. The Louisiana Purchase was by far the largest territorial gain in United States history, stretching from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains. After Louisiana became a state the Purchase was renamed the Missouri Territory by Congress in June 1812. This sparked a debate in Washington as to whether the Missouri Territory would be free or slave. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s brother, Henry Ward described it as, “The whole nation lies spread out like a gambler’s table”.

During the 1840s there was a push to organize the Kansas and Nebraska territories as part of a plan to build a transcontinental railroad. The question of whether the rail line should pass through northern free territory or southern slave territory was hotly debated. It became clear that no progress on the railroad could be made unless the limits on slavery articulated in the Missouri Compromise could be removed. Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas proposed a bill that offered residents of the Kansas and Nebraska territories a choice as to whether they would permit or reject slavery on their soil. The fine details of the bill led Northerners and Southerners to find self interested reasons to deny its passage. Moved by the immorality of slavery and angered by the Compromise of 1850, Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin. When it was published as a two-volume work in 1852 it proved to be extremely popular in England. In May, 1853, during a visit to England, Stowe was presented with a petition signed by over a half million British women. This petition was titled, "An Affectionate and Christian Address of Many Thousands of Women of Great Britain and Ireland to Their Sisters the Women of the United States of America.” The women of Britain hoped the petition would rouse women in the United States to the anti-slavery cause. In response, Stowe promised to establish a committee of women in America to generate support for abolition. The effort proved unsuccessful as Stowe had no strong connections to either established women's organizations or anti-slavery groups. However in March, 1854, Stowe published “An Appeal to the Women of the Free States of America on the Present Crisis in Our Country.” She urged women to petition, organize, and pray to prevent slavery in the nascent states of the Missouri Territory. (see reference below for this publication) After much debate, The Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed by Congress on May 30, 1854, and signed by President Franklin Pierce. It divided the region along the 40th parallel, with Kansas to the South and Nebraska to the North. It did allow people in the territories of Kansas and Nebraska to decide for themselves whether or not to allow slavery within their borders. The Act served to repeal the Missouri Compromise of 1820 which prohibited slavery north of latitude 36°30´. President Pierce and Senator Douglas hoped that, “Popular Sovereignty” would help bring an end to the national debate over slavery, but the Kansas–Nebraska Act outraged many Northerners, giving rise to the anti-slavery Republican Party. After passage of the act, pro- and anti-slavery elements flooded into Kansas with the goal of establishing a population that would vote for or against slavery. The result was a series of armed conflicts known as "Bleeding Kansas". Sources: Harriet Beecher Stowe: A life by Joan Hedrick published 1994 by Oxford University press https://www.accessible-archives.com/2012/03/an-appeal-to-the-women-of-the-free-states-of-america/ https://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/kansas.html About the author: Dr. Nicholas Andreadis is a volunteer at the Harriet Beecher Stowe House. He was a professor and dean at Western Michigan University prior to moving to Cincinnati. |

Archives

March 2025

Categories

All

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed