The Missouri Compromise (link to prior post) achieved what senators desired, a balance of powers aligned for and against the institution of slavery. By the late 1840s, The United States was composed of 30 states - 15 free and 15 slave. The balance was about to be upset. In January 1848, gold had been discovered on the American River near Sacramento and the influx of people began. Days later, the treaty ending the Mexican War gave the United States a large part of the Southwest, including present day California. In 1849, Californians petitioned for statehood as a free state, igniting debate and ultimately the Compromise of 1850. At the same time, Texas claimed territory extending all the way to Santa Fe. In January 1850, the venerable Kentucky Senator Henry Clay presented a bill that would leave the question of slavery off the table the territories of New Mexico, Nevada, Arizona, and Utah until each applied for statehood. In addition, the slave trade would be abolished in the District of Columbia, although slavery would still be permitted in the nation’s capitol. It was agreed that California would be admitted as a free state, but the accompanying Fugitive Slave Act was passed to satisfy pro-slavery states. The act called for changes that made the process for filing a claim against a fugitive easier for slave owners and citizens were required to aid in the recovery of fugitive slaves. A federal commissioner was appointed to hear a case and determine an African American's status as a slave or free person. The slave owner was responsible for paying the commissioner. If the commissioner ruled in favor of the white man, the commissioner received ten dollars. If he ruled against the slaveholder, the commissioner earned only five dollars. Fugitives had no right to a jury trial and could not present evidence. Anyone caught hiding or assisting fugitive slaves faced stiff penalties. Northern abolitionists opposed this law and tried to insert protections into the bill for African Americans. They wanted the Fugitive Slave Law to guarantee African Americans the right to testify and also the right to a trial by jury. Other legislators refused and claimed that African Americans were not United States citizens. Between 1850 and 1860, 343 African Americans appeared before federal commissioners. Of those 343 people, 332 African Americans were sent to slavery in the South. The commissioners allowed only eleven people to remain free in the North. Some people who had been free for their entire lives left the country for Canada. Even free blacks, too, were captured and sent to the South, completely defenseless with no legal rights. Abolitionists challenged the Fugitive Slave Law's legality in court, but the United States Supreme Court upheld the law's constitutionality in 1859. Ohio abolitionists encouraged people to oppose any attempts to enforce it and referred to the legislation as the "Kidnap Law.” The act enraged author Harriet Beecher Stowe and its passage is attributed to have caused her to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The compromise lasted until the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, when Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas proposed legislation allowing the issue of slavery to be decided in the new territories. The acts were eventually repealed, but not until June of 1864. Sources: The War Before the War by Andrew Delbanco (2018) Penguin Press https://ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Fugitive_Slave_Law_of_1850 About the author:

Dr. Nicholas Andreadis is a volunteer at the Harriet Beecher Stowe House. He was a professor and dean at Western Michigan University prior to moving to Cincinnati.

3 Comments

Herman Melville, Moby Dick and "Benito Cereno" Herman Melville was a New Yorker who went to sea, and Harriet Beecher Stowe was a New Englander who spent eighteen important years in Cincinnati. It’s unlikely that Harriet read Melville’s books, and Melville may have read Uncle Tom’s Cabin but only after writing Moby-Dick. Still, these two authors have more in common than you might think. Both were raised in Calvinist households, Melville in the Dutch Reformed Church and Harriet in her father’s Presbyterianism. Both also later switched to churches with more optimistic theologies, Melville to Unitarianism and Harriet to the Episcopal Church. Scholar David Reynolds suggests that the gloomy Calvinist background and the spiritual questioning that followed account for the surprising number of characters who question their faith in Uncle Tom’s Cabin: “Push Uncle Tom’s Cabin a bit more toward the dark side and we’re in the doubt-riddled world of Melville, Hawthorne, and Dickinson.” The year 1851 was central to the writing lives of both Harriet and Melville. She began serial publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and he published Moby-Dick. Both authors followed these works with important fictional treatments of slavery in the mid-1850s: Melville with his novella “Benito Cereno” in 1855 and Harriet with her novel Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp the next year. The two authors’ very different approaches to writing made both their critical and popular reputations as volatile as today’s stock market. Harriet’s direct condemnation of slavery in Uncle Tom’s Cabin made it the bestselling book in the world other than the Bible in the nineteenth century, while Melville’s dense language, irony, and ambiguous symbolism in Moby-Dick attracted few readers in his lifetime. His contemporaries also were not ready for the close crosscultural friendship of Ishmael and Queequeg or Melville’s implicit critique of American white supremacy when Ishmael says: “It was the whiteness of the whale that above all things appalled me.” Even when Melville dealt explicitly with slavery in “Benito Cereno,” his irony and complex character development were too indirect to interest abolitionists or many other readers. When Melville and Harriet died in the 1890s, she was by far the more famous of the two. By the 1920s, literary tastes were changing. Critics began to celebrate Melville’s psychological analysis and thematic ambiguities and turned away from what they considered the propaganda and sentimentality of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Then, starting in the early 1980s, feminist criticism and cultural studies brought Uncle Tom’s Cabin back into the literary canon, where it stands today alongside Moby-Dick as one of the central works of mid-nineteenth century American literature. About the author:

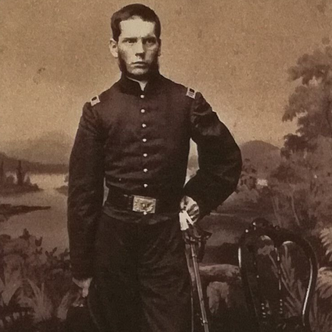

Dr. John Getz, Professor Emeritus, Xavier University, retired in 2017 after teaching English there for 45 years. He specializes in American literature, especially nineteenth century, as well as the intersections of literature and peace studies. He has written articles on a variety of authors including Edith Wharton, Sherwood Anderson, and Ursula Le Guin. He appears in the documentary film Becoming Harriet Beecher Stowe, scheduled for release in 2020 by Fourth Wall Films.  detail image from HBHS exhibit To Give It All to This Cause detail image from HBHS exhibit To Give It All to This Cause Frederick William Stowe was Harriet Beecher Stowe and Calvin Stowe’s fourth of seven children. Born in 1840, Frederick was twelve years old by the time Harriet published Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1852. Frederick was often separated from Harriet and Calvin, due to Calvin’s frequent business trips to Europe and several family tragedies. Cholera was common in the nineteenth century, and especially in Cincinnati. Harriet herself even caught cholera. When Frederick was nine years old, Harriet’s third son, Samuel Charles, died as an infant due to Cholera. Frederick often suffered from a lack of attention from his mother, and by the time he was sixteen, Frederick had already become an alcoholic. While Harriet was off on a European tour in the 1850s, Frederick was sent to his uncle, Rev. Thomas Beecher, who had experience helping people with addictions recover. Frederick was a patient of the “water cure”, a popular method at the time. By drinking large amounts of water and taking frequent baths, patients would purify their bodies of all harmful substances. Frederick made a lot of progress and was reaching the point of becoming fully sober. Frederick at age seventeen had a setback, when his oldest brother Henry Ellis drowned in the Connecticut River. Joining Harriet and some other siblings on another European tour in 1859 and 1860, Frederick expressed positivity and hope for the future in letters to Calvin. With his return to the United States, Frederick decided to become a doctor and enrolled at Harvard medical school. After less than a semester at Harvard, Frederick’s life, along with thousands of others, suddenly changed. Frederick, at the age of twenty-one, became a part of the 1st Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry and was one of the initial 75,000 volunteers called for by Abraham Lincoln. While Harriet was worried about “the temptations of the camp” (meaning alcohol), she visited him before he marched off, describing him as “in high spirits.” Serving in the Union army was certainly the high point of Frederick’s life. After a skirmish, Frederick participated in the First Battle of Bull Run. After Bull Run, Frederick’s spirits dropped for two years, as he transferred from the 1st Massachusetts Infantry to the Heavy Artillery regiment, spending the majority of his time in Union camps and forts. Harriet later received a letter from Frederick describing how boring and repetitive camp life was. She decided to act. After a letter to Harriet’s friend, Brig. Gen. Adolph von Steinwehr, Frederick was moved and promoted to Captain within the XI Corps of the Army of the Potomac. Frederick was a part of the general’s staff, and as such was exempt from combat (A sneaky move from Harriet). This changed at the battle of Gettysburg. As Frederick went into combat again, he was wounded by a fragment from a shell. Frederick’s luck, bad as it always was, failed him yet again. Frederick did recover, slowly and over several months. He was later discharged from the army, as it was clear he was in no shape to go back to fighting. Frederick returned to his parents, but he soon relapsed into alcoholism. Harriet had not given up and sent him to manage a citrus farm in Florida. Frederick did not do well and was later sent to another alcoholism treatment center, but to no avail. Frederick decided to sail to San Francisco. He arrived but then disappeared. He did mention becoming a sailor, but what happened to him is unknown. Despite several investigations by the Stowes, his fate remains unknown. Given the incredible loss of siblings and the time with his parents, one may understand why he turned to alcohol as an effort to escape. With his mother becoming one of the most famous women of the nineteenth century, he must have felt that she was on a plane at an unreachable height above him. I’m sure that this was part of the reason he joined the army, to make her proud. About the author: Emmett Looman is a Youth Docent at the Harriet Beecher Stowe House in Cincinnati. He enjoys history and is always happy to learn new interesting facts about the past. Sources: https://www.historynet.com/frederick-stowe-in-the-shadow-of-uncle-toms-cabin-january-99-americas-civil-war-feature.htm https://www.geni.com/people/Lt-Frederick-Stowe-USA/6000000000699446385 http://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/35123 http://www.mainelegacy.com/8.html https://www.andoverlestweforget.com/faces-of-andover/stowe-tyer/frederick-stowe/ https://www.harrietbeecherstowecenter.org/harriet-beecher-stowe/family/ With the Hamilton musical coming to TV today, have you remembered the connection between this famous duel and Lyman Beecher? His sermon "The Remedy for Duelling" (his spelling) met the country in a moment of moral upheaval over the practice of dueling and the support of those who participated in it. The entire Beecher family would become known for their leadership and opinions on national moral conversations, from dueling to slavery, temperance, women's suffrage, and more.

You can see the full historical document here: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc2.ark:/13960/t2p55q46j&view=1up&seq=8 But wait, there's more! Our volunteer community had a lot to share about what books and resources have made a difference for them in understanding the historical context of racial injustice. If you haven't seen it, check out We Keep Learning: Part I.

We are continual learners who strive to connect others to resources that our board, volunteers, and staff are finding helpful in that quest. We are currently reading, following, and listening to: Brynn:

Haley:

John: Films Amazing Grace (based on the origin of the hymn and the fight to end the British slave trade) Amistad (based on the famous 1839 rebellion on a slave ship and the aftermath) Almos’ a Man (based on Richard Wright’s short story; PBS American Short Story Film Series) The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman (based on the novel by Ernest J. Gaines) Do the Right Thing (written, produced, and directed by Spike Lee) I Am Not Your Negro (documentary based on an unfinished manuscript by James Baldwin) Essays Frederick Douglass, “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time and Notes of a Native Son Alice Walker, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose, especially the title essay Ta-Nehisi Coates, Between the World and Me Eve Fairbanks, “The ‘Reasonable’ Rebels,” Washington Post, 8/29/2019 Autobiography Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl Malcolm X with Alex Haley, The Autobiography of Malcolm X (also Spike Lee’s film Malcolm X) Maya Angelou, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (also the film) Melba Pattillo Beals, Warriors Don’t Cry Short Fiction James Baldwin, “Sonny’s Blues” Langston Hughes, The Best of Simple Novels Charles Chesnutt, The Marrow of Tradition Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man Chinua Achebe, Things Fall Apart Toni Morrison, Song of Solomon and Beloved Ernest J. Gaines, A Gathering of Old Men and A Lesson Before Dying Octavia Butler, Kindred Caryl Phillips, Crossing the River Nnedi Okorafor, The Binti Trilogy: Binti, Binti: Home, Binti: The Night Masquerade Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Americanah Poems Paul Laurence Dunbar, “We Wear the Mask” Langston Hughes, Montage of a Dream Deferred Robert Hayden, “Those Winter Sundays” Experiences Seeing the signs for “White” and “Colored” as a child traveling in the South with my parents in the 1950s Teaching in the Xavier University E Pluribus Unum Program decades ago Listening to African American faculty and students at Xavier over the years Taking the 21-Day Racial Equity and Social Justice Challenge from the Cleveland YWCA in 2019 Docenting and leading discussions at Harriet Beecher Stowe House Harriet wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1851-52 to draw light to the injustices of her own time. With the current challenges our nation faces, we are reminded that the legacy of Harriet's time still interferes with our nation’s journey towards an equitable society.

The Friends of Harriet Beecher Stowe House community values the ideas of historical literacy (http://stowehousecincy.org/aboutus.html. ) As part of our lead-in week to Harriet’s Virtual Birthday Party on Sunday June 14th, we want to share ideas and resources we have found helpful in our own learning process. We are continual learners who strive to connect others to resources that our board, volunteers, and staff are finding helpful in that quest. We are currently reading, following, and listening to: Abigail:

Christina:

Fred:

Robin:

|

Archives

March 2025

Categories

All

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed