Abolitionists Walking Tour: Walnut Hills

Walnut Hills Presbyterian Church (2601 Gilbert Avenue)

Eastern side of the tower (wikipedia.org)

Eastern side of the tower (wikipedia.org)

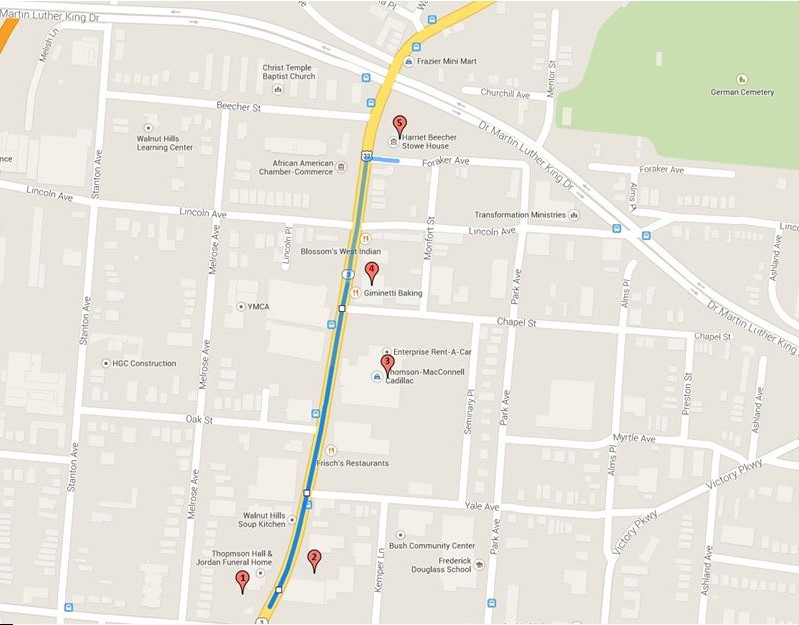

The Walnut Hills Presbyterian Church's impressive Gothic tower still stands on the corner of Taft and Gilbert. The church was founded in 1819 by a group that included Reverend James Kemper. The Kemper family played an important role in shaping Walnut Hills and its institutions.

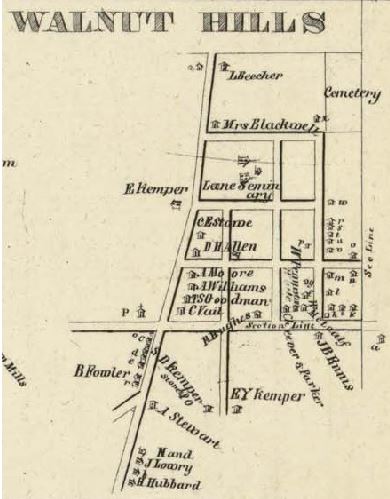

Reverend James Kemper and his family moved to Cincinnati in 1791 and built a log cabin on the corner of what is now Kemper Lane and Windsor Street. They had bought 150 acres from John Cleves Symmes, one of the largest land owners in the Cincinnati area at that time. They established their farmstead here and named it Walnut Hill, which comprises most of the neighborhood of Walnut Hills today.

The Kempers had a mission for Walnut Hills that included faith, freedom, and education. In 1819, Rev. James Kemper helped to establish the First Presbyterian Church of Walnut Hills. The remaining tower of the church still exists today at the corner of William Howard Taft and Gilbert Avenue. The Kempers sold some of their land in 1829 to the Lane brothers, who opened the Lane Theological Seminary. The Seminary would become a center of controversy during the 1834 Lane Debates over slavery and abolition. The Seminary eventually merged with the Presbyterian Church in 1878. John Kemper’s sons sold off much of their land for development, and as the neighborhood grew, Walnut Hills became one of the most religiously and ethnically diverse neighborhoods of the time.

Quotes:

“It is confidently alleged that but for the presence of Mr. Kemper and his family in the town of Cincinnati, ready to begin the building of a church, and his example rallying his people to give succor to the sick, wounded, weary and distraught army of St. Clair, the entire population would have stampeded south of the Ohio. He was always afterwards held in the highest esteem among the [Native Americans] for his bravery.” — Andrew Carr Kemper, A Memorial of the Rev. James Kemper for the Centennial of the Synod of Kentucky, 1899. p. 10.

“[Kemper] was winning in his manners and slow to speak…. He was not pretentious, brilliant, or profound, but plain, simple, unassuming, ready and reliable, and endued with an exquisite common sense…. He was hopeful and cheerful, never cast down.” — Andrew Carr Kemper, A Memorial of the Rev. James Kemper for the Centennial of the Synod of Kentucky, 1899. p. 11.

“In Ohio, [Kemper] became the conspicuous leader and promoter of religious education, always inciting others to action as if from their own motive, rather than appearing himself to the one commanding person. This was the stamp of his genius….” — Andrew Carr Kemper, A Memorial of the Rev. James Kemper for the Centennial of the Synod of Kentucky, 1899. p. 16.

Sources:

Cincinnati 45206: Template for Tomorrow. Cincinnati: Definitive Works, 2006. Print.

Cincinnati Preservation Association. Walking Tour of Walnut Hills. Cincinnati: Cincinnati Preservation Association, n.d. Print.

Kemper, Andrew Carr. A Memorial of the Rev. James Kemper for the Centennial of the Synod of Kentucky. 1899. https://books.google.com/books?id=zllDAAAAYAAJ

Reverend James Kemper and his family moved to Cincinnati in 1791 and built a log cabin on the corner of what is now Kemper Lane and Windsor Street. They had bought 150 acres from John Cleves Symmes, one of the largest land owners in the Cincinnati area at that time. They established their farmstead here and named it Walnut Hill, which comprises most of the neighborhood of Walnut Hills today.

The Kempers had a mission for Walnut Hills that included faith, freedom, and education. In 1819, Rev. James Kemper helped to establish the First Presbyterian Church of Walnut Hills. The remaining tower of the church still exists today at the corner of William Howard Taft and Gilbert Avenue. The Kempers sold some of their land in 1829 to the Lane brothers, who opened the Lane Theological Seminary. The Seminary would become a center of controversy during the 1834 Lane Debates over slavery and abolition. The Seminary eventually merged with the Presbyterian Church in 1878. John Kemper’s sons sold off much of their land for development, and as the neighborhood grew, Walnut Hills became one of the most religiously and ethnically diverse neighborhoods of the time.

Quotes:

“It is confidently alleged that but for the presence of Mr. Kemper and his family in the town of Cincinnati, ready to begin the building of a church, and his example rallying his people to give succor to the sick, wounded, weary and distraught army of St. Clair, the entire population would have stampeded south of the Ohio. He was always afterwards held in the highest esteem among the [Native Americans] for his bravery.” — Andrew Carr Kemper, A Memorial of the Rev. James Kemper for the Centennial of the Synod of Kentucky, 1899. p. 10.

“[Kemper] was winning in his manners and slow to speak…. He was not pretentious, brilliant, or profound, but plain, simple, unassuming, ready and reliable, and endued with an exquisite common sense…. He was hopeful and cheerful, never cast down.” — Andrew Carr Kemper, A Memorial of the Rev. James Kemper for the Centennial of the Synod of Kentucky, 1899. p. 11.

“In Ohio, [Kemper] became the conspicuous leader and promoter of religious education, always inciting others to action as if from their own motive, rather than appearing himself to the one commanding person. This was the stamp of his genius….” — Andrew Carr Kemper, A Memorial of the Rev. James Kemper for the Centennial of the Synod of Kentucky, 1899. p. 16.

Sources:

Cincinnati 45206: Template for Tomorrow. Cincinnati: Definitive Works, 2006. Print.

Cincinnati Preservation Association. Walking Tour of Walnut Hills. Cincinnati: Cincinnati Preservation Association, n.d. Print.

Kemper, Andrew Carr. A Memorial of the Rev. James Kemper for the Centennial of the Synod of Kentucky. 1899. https://books.google.com/books?id=zllDAAAAYAAJ

Calvin and Harriet Beecher Stowe House (2622 Gilbert Avenue)

Calvin Stowe (commons.wikipedia.org)

Calvin Stowe (commons.wikipedia.org)

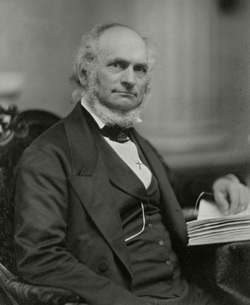

The home of abolitionist writer Harriet Beecher Stowe and her husband, Calvin Stowe, saw the Stowes emerge as antislavery and education advocates. Although the home no longer stands, the impact of its inhabitants is lasting.

Calvin Stowe moved to Walnut Hills in 1832 when he was appointed as a professor at Lane Seminary.He was married to Eliza Tyler, who became very close friends with Harriet Beecher. Eliza passed away in 1834 and two years later, in January of 1836, Calvin and Harriet were married. Although it would have been likely that both Calvin and Harriet lived in the Beecher’s home as newlyweds, they did eventually move to their own home on the Lane Seminary grounds. It is believed to be where the Assumption of The Blessed Virgin Mary Parish resides today.

While in Cincinnati, Calvin became an important leader in the development of free public schools to integrate new immigrants into American society, especially in the western states. He traveled to England and Europe several times to study education systems. Calvin Stowe also and promoted state-supported education and teacher training back in the United States.

Although they spent much time apart, Calvin and Harriet’s marriage was an alliance of American social reform and freedom that would change history. While away, Calvin wrote letters to Harriet about the British Antislavery Movement. Harriet published excerpts of these letters in the Cincinnati Journal. Harriet took on roles as a mother, domestic keeper, and writer, all to support the family while Calvin was working for small wages at the Seminary.

In 1850 Harriet and the children moved out of Cincinnati after hard times with little money and the loss of Harriet’s youngest child, Samuel Charles, to the cholera epidemic of 1849. The struggles followed the Stowes to Maine, where Calvin had accepted another teaching position. Harriet continued writing, however, and while in a church service became inspired to write a story based on her experience with the antislavery movement. Little did she know that this idea would develop into a novel called Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which would become a best seller and catalyst to the Civil War.

Within the first year of the publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, it sold 300,000 copies. It was eventually translated into 75 different languages. Not only did the Stowe’s thrive financially, but Harriet became a household name and leader in the anti-slavery movement. Uncle Tom’s Cabin became one of the most controversial and influential books in American history.

Quote:

Calvin Stowe was “rich in Greek and Hebrew, Latin and Arabic, and alas! rich in little else….” — Harriet Beecher Stowe. 1853 letter. As quoted in Earle Hilgert, “Calvin Ellis Stowe, Pioneer Librarian of the Old West.” The Library Quarterly: Information Community, Policy, vol 50, no 30 (July 1980). p. 324.

Sources:

Haugen, Brenda. Harriet Beecher Stowe: Author and Advocate. Minneapolis, MN: Compass Point, 2005. Print.

Hedrick, Joan D. Harriet Beecher Stowe: A Life. New York: Oxford UP, 1994. Print.

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/567807/Calvin-E-Stowe

http://www.ants.edu/stowe

Earle Hilgert, “Calvin Ellis Stowe, Pioneer Librarian of the Old West.” The Library Quarterly: Information Community, Policy, vol 50, no 30 (July 1980). p. 324. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4307247

Calvin Stowe moved to Walnut Hills in 1832 when he was appointed as a professor at Lane Seminary.He was married to Eliza Tyler, who became very close friends with Harriet Beecher. Eliza passed away in 1834 and two years later, in January of 1836, Calvin and Harriet were married. Although it would have been likely that both Calvin and Harriet lived in the Beecher’s home as newlyweds, they did eventually move to their own home on the Lane Seminary grounds. It is believed to be where the Assumption of The Blessed Virgin Mary Parish resides today.

While in Cincinnati, Calvin became an important leader in the development of free public schools to integrate new immigrants into American society, especially in the western states. He traveled to England and Europe several times to study education systems. Calvin Stowe also and promoted state-supported education and teacher training back in the United States.

Although they spent much time apart, Calvin and Harriet’s marriage was an alliance of American social reform and freedom that would change history. While away, Calvin wrote letters to Harriet about the British Antislavery Movement. Harriet published excerpts of these letters in the Cincinnati Journal. Harriet took on roles as a mother, domestic keeper, and writer, all to support the family while Calvin was working for small wages at the Seminary.

In 1850 Harriet and the children moved out of Cincinnati after hard times with little money and the loss of Harriet’s youngest child, Samuel Charles, to the cholera epidemic of 1849. The struggles followed the Stowes to Maine, where Calvin had accepted another teaching position. Harriet continued writing, however, and while in a church service became inspired to write a story based on her experience with the antislavery movement. Little did she know that this idea would develop into a novel called Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which would become a best seller and catalyst to the Civil War.

Within the first year of the publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, it sold 300,000 copies. It was eventually translated into 75 different languages. Not only did the Stowe’s thrive financially, but Harriet became a household name and leader in the anti-slavery movement. Uncle Tom’s Cabin became one of the most controversial and influential books in American history.

Quote:

Calvin Stowe was “rich in Greek and Hebrew, Latin and Arabic, and alas! rich in little else….” — Harriet Beecher Stowe. 1853 letter. As quoted in Earle Hilgert, “Calvin Ellis Stowe, Pioneer Librarian of the Old West.” The Library Quarterly: Information Community, Policy, vol 50, no 30 (July 1980). p. 324.

Sources:

Haugen, Brenda. Harriet Beecher Stowe: Author and Advocate. Minneapolis, MN: Compass Point, 2005. Print.

Hedrick, Joan D. Harriet Beecher Stowe: A Life. New York: Oxford UP, 1994. Print.

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/567807/Calvin-E-Stowe

http://www.ants.edu/stowe

Earle Hilgert, “Calvin Ellis Stowe, Pioneer Librarian of the Old West.” The Library Quarterly: Information Community, Policy, vol 50, no 30 (July 1980). p. 324. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4307247

Lane Theological Seminary (2820 Gilbert Avenue)

Lane Seminary (commons.wikipedia.org)

Lane Seminary (commons.wikipedia.org)

The Lane Theological Seminary was home to controversial debates over slavery in 1834, perhaps the first public discussion of the topic. Although only the steps of the seminary remain today, it had a great influence on the religious life of Cincinnati and the frontier West of the 1800s.

The Lane Theological Seminary was established in 1829 as a school to educate new ministers and spread Presbyterianism in the developing Western states. It was named after two Baptist brothers from New Orleans, Ebenezer and William Lane, who pledged $4,000 for the start of the school. Lyman Beecher became the first president of the Seminary, and through his social activism on the pressing social and theological conflicts affecting the Cincinnati Area at that time, Lane Seminary became a vibrant center for these controversial issues.

In 1834, the Lane Seminary held an 18 day debate on slavery, known as the first public discussion on that topic. Issues discussed at the debate included the abolishment of slavery and opposition to American colonization. A radical group of students, led by Theodore Dwight Weld, emerged during these debates and became known as the “Lane Rebels.” Their radical demands for the immediate emancipation of slaves worried Beecher because they challenged the authority of the school. This conflict led to the departure of the group to Oberlin College, which became an interracial institution dedicated to the emancipation and education of African-Americans.

In 1852, Lyman Beecher resigned as president of the seminary and moved back East to be with his son, Rev. Henry Ward Beecher. The seminary struggled financially and was eventually absorbed by the McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago in 1932. The last standing building of the seminary was the Westminster Buildings, which were dormitories that were converted into apartments in 1933. By 1956 the seminary was completely demolished, and today the Thompsen-MacConnell Cadillac dealership now stands on the old Seminary grounds. The stairs that lead up to the seminary can still be seen surrounding the dealership today.

Quotes:

The Lane Seminary was “an institution freighted with the spiritual interests of the West…. The Valley was our expected field; we assembled here, that we might the more accurately learn its character, catch the spirit of the gigantic enterprise, grow up into its genius, appreciate its peculiar wants, and be thus qualified by practical skill, no less than by theological erudition, to wield the weapons of truth.” — “Defence of the Students.” The Liberator, vol 5. no 2, Jan 10, 1835. pp. 5-6. http://www.oberlin.edu/external/EOG/LaneDebates/RebelsDefence.htm

“With the same spirit of free inquiry, we discussed the question of slavery. We prayed much, heard facts, weighed arguments, kept our temper, and after the most patient pondering, in which we were sustained by the excitement of sympathy, not of anger, we decided that slavery was a sin, and as such, ought to be immediately renounced. In this case, too, we acted. We organized an anti-slavery society, and published facts, arguments, remonstrances and appeals.” — “Defence of the Students.” The Liberator, vol 5. no 2, Jan 10, 1835. pp. 5-6.

Sources:

Cincinnati; a Guide to the Queen City and Its Neighbors. Cincinnati: Wiesen-Hart, 1943. Print.

Robert S. Fletcher (1943). The Test of Academic Freedom. A History of Oberlin College From Its Foundation Through the Civil War.

“Defence of the Students.” The Liberator, vol 5. no 2, Jan 10, 1835. pp. 5-6. http://www.oberlin.edu/external/EOG/LaneDebates/RebelsDefence.htm

The Lane Theological Seminary was established in 1829 as a school to educate new ministers and spread Presbyterianism in the developing Western states. It was named after two Baptist brothers from New Orleans, Ebenezer and William Lane, who pledged $4,000 for the start of the school. Lyman Beecher became the first president of the Seminary, and through his social activism on the pressing social and theological conflicts affecting the Cincinnati Area at that time, Lane Seminary became a vibrant center for these controversial issues.

In 1834, the Lane Seminary held an 18 day debate on slavery, known as the first public discussion on that topic. Issues discussed at the debate included the abolishment of slavery and opposition to American colonization. A radical group of students, led by Theodore Dwight Weld, emerged during these debates and became known as the “Lane Rebels.” Their radical demands for the immediate emancipation of slaves worried Beecher because they challenged the authority of the school. This conflict led to the departure of the group to Oberlin College, which became an interracial institution dedicated to the emancipation and education of African-Americans.

In 1852, Lyman Beecher resigned as president of the seminary and moved back East to be with his son, Rev. Henry Ward Beecher. The seminary struggled financially and was eventually absorbed by the McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago in 1932. The last standing building of the seminary was the Westminster Buildings, which were dormitories that were converted into apartments in 1933. By 1956 the seminary was completely demolished, and today the Thompsen-MacConnell Cadillac dealership now stands on the old Seminary grounds. The stairs that lead up to the seminary can still be seen surrounding the dealership today.

Quotes:

The Lane Seminary was “an institution freighted with the spiritual interests of the West…. The Valley was our expected field; we assembled here, that we might the more accurately learn its character, catch the spirit of the gigantic enterprise, grow up into its genius, appreciate its peculiar wants, and be thus qualified by practical skill, no less than by theological erudition, to wield the weapons of truth.” — “Defence of the Students.” The Liberator, vol 5. no 2, Jan 10, 1835. pp. 5-6. http://www.oberlin.edu/external/EOG/LaneDebates/RebelsDefence.htm

“With the same spirit of free inquiry, we discussed the question of slavery. We prayed much, heard facts, weighed arguments, kept our temper, and after the most patient pondering, in which we were sustained by the excitement of sympathy, not of anger, we decided that slavery was a sin, and as such, ought to be immediately renounced. In this case, too, we acted. We organized an anti-slavery society, and published facts, arguments, remonstrances and appeals.” — “Defence of the Students.” The Liberator, vol 5. no 2, Jan 10, 1835. pp. 5-6.

Sources:

Cincinnati; a Guide to the Queen City and Its Neighbors. Cincinnati: Wiesen-Hart, 1943. Print.

Robert S. Fletcher (1943). The Test of Academic Freedom. A History of Oberlin College From Its Foundation Through the Civil War.

“Defence of the Students.” The Liberator, vol 5. no 2, Jan 10, 1835. pp. 5-6. http://www.oberlin.edu/external/EOG/LaneDebates/RebelsDefence.htm

Elizabeth Blackwell House (2900 Gilbert Avenue)

Elizabeth Blackwell (wikipedia.org)

Elizabeth Blackwell (wikipedia.org)

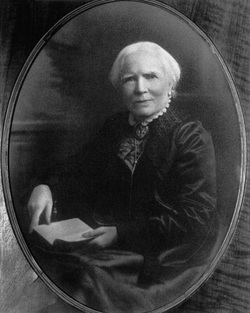

This site was home to Elizabeth Blackwell, who became the first female physician in the United States, during some of Blackwell’s formative years.

Elizabeth Blackwell moved with her family to Cincinnati in 1838 as they attempted to revive a sugar refinery business that had been unsuccessful in New York. Her father, Samuel Blackwell influenced his children greatly with his liberal views including anti-slavery sentiments. Cincinnati was interesting to the family not only as one of the centers for the abolition movement, but also as a place to practice cultivating sugar beets, an alternative to the production of sugar cane which was slave-labor intensive. Unfortunately Samuel Blackwell passed away three weeks after moving to Cincinnati.

In an attempt to support the family, the Blackwell sisters opened the Cincinnati English and French Academy for Young Ladies in their own home. In 1844, Elizabeth pursued a teaching job in Henderson, Kentucky, where Elizabeth was exposed to the shocking realities of slavery in the South. After her teaching contract was up, she returned to Cincinnati to join her family in their new home in Walnut Hills. While living in Walnut Hills, Elizabeth met Harriet Beecher Stowe and her family, with whom she became close and shared her interest in the abolition movement. She also met Mary Donaldson, a neighbor who was suffering from cancer. Mary is the first person to suggest to Elizabeth that she become a physician. Elizabeth was initially repulsed by the idea of becoming a doctor, but after another teaching position in Asheville, North Carolina, she was convinced by the horrible conditions and treatment of slaves that she must pursue a career in the medical field.

Pursuing a career as a physician was a difficult task for a woman at the time. This was mainly due to stereotypes of women being less capable then men in the male-dominated medical field. While teaching in Asheville, Elizabeth earned enough money to cover the expenses of medical school. She was accepted by Geneva Medical College in New York and influenced the behavior and intentions of her surrounding class of young men. In January of 1849, Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman to graduate with a medical degree in the United States.

Quote:

“I longed to jump up, and taking the chains from those injured, unmanned men, fasten them on their tyrants till they learned . . . the bitterness of [slavery].” Elizabeth Blackwell, as quoted in Barbara A Somervil, Elizabeth Blackwell: America’s First Female Doctor. p. 31.

Sources:

Curtis, Robert H. (1993). Great Lives: Medicine. New York, New York: Atheneum Books for Young Readers.

Smith, Stephen. Letter. The Medical Co-education of the Sexes. New York Church Union. 1892

Somervill, Barbara A. Elizabeth Blackwell: America's First Female Doctor. Pleasantville, NY: Gareth Stevens Pub., 2009. Print. or https://books.google.com/books?isbn=1433900556

Elizabeth Blackwell moved with her family to Cincinnati in 1838 as they attempted to revive a sugar refinery business that had been unsuccessful in New York. Her father, Samuel Blackwell influenced his children greatly with his liberal views including anti-slavery sentiments. Cincinnati was interesting to the family not only as one of the centers for the abolition movement, but also as a place to practice cultivating sugar beets, an alternative to the production of sugar cane which was slave-labor intensive. Unfortunately Samuel Blackwell passed away three weeks after moving to Cincinnati.

In an attempt to support the family, the Blackwell sisters opened the Cincinnati English and French Academy for Young Ladies in their own home. In 1844, Elizabeth pursued a teaching job in Henderson, Kentucky, where Elizabeth was exposed to the shocking realities of slavery in the South. After her teaching contract was up, she returned to Cincinnati to join her family in their new home in Walnut Hills. While living in Walnut Hills, Elizabeth met Harriet Beecher Stowe and her family, with whom she became close and shared her interest in the abolition movement. She also met Mary Donaldson, a neighbor who was suffering from cancer. Mary is the first person to suggest to Elizabeth that she become a physician. Elizabeth was initially repulsed by the idea of becoming a doctor, but after another teaching position in Asheville, North Carolina, she was convinced by the horrible conditions and treatment of slaves that she must pursue a career in the medical field.

Pursuing a career as a physician was a difficult task for a woman at the time. This was mainly due to stereotypes of women being less capable then men in the male-dominated medical field. While teaching in Asheville, Elizabeth earned enough money to cover the expenses of medical school. She was accepted by Geneva Medical College in New York and influenced the behavior and intentions of her surrounding class of young men. In January of 1849, Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman to graduate with a medical degree in the United States.

Quote:

“I longed to jump up, and taking the chains from those injured, unmanned men, fasten them on their tyrants till they learned . . . the bitterness of [slavery].” Elizabeth Blackwell, as quoted in Barbara A Somervil, Elizabeth Blackwell: America’s First Female Doctor. p. 31.

Sources:

Curtis, Robert H. (1993). Great Lives: Medicine. New York, New York: Atheneum Books for Young Readers.

Smith, Stephen. Letter. The Medical Co-education of the Sexes. New York Church Union. 1892

Somervill, Barbara A. Elizabeth Blackwell: America's First Female Doctor. Pleasantville, NY: Gareth Stevens Pub., 2009. Print. or https://books.google.com/books?isbn=1433900556

Harriet Beecher Stowe House (2950 Gilbert Avenue)

Harriet Beecher Stowe House (photo by Chis DeSimio)

Harriet Beecher Stowe House (photo by Chis DeSimio)

The Harriet Beecher Stowe House, which still stands, hosted educators, ministers, and antislavery advocates in the 18 years the Beechers called Walnut Hills home.

The Harriet Beecher Stowe House was the official residence of the Lane Seminary president. Harriet's father, Rev. Lyman Beecher, was the home's first resident.

Rev. Lyman Beecher was a leader in the Second Great Awakening, a Protestant revival movement during the early nineteenth century. This movement brought the Beechers to Cincinnati so that Lyman Beecher could pursue his mission in training ministers at the Lane Seminary to “win the West in Protestantism.” His eldest daugter, Catharine Beecher was a female educator and writer who founded several female high schools and colleges, including the Western Female Institute that was once located in downtown Cincinnati. Lyman Beecher's son Henry Ward Beecher was an American clergyman as well as a social reformer and speaker. He is best known for theological approaches that emphasized God’s love and his support for the abolition of slavery.

Although Harriet married Calvin Stowe in 1836 and moved to a nearby property on the Lane Seminary grounds, she frequently visited her father’s home, and likely gave birth to her first two children in the upstairs bedroom. Harriet and her family lived in Cincinnati for 18 years, and were influenced by their experience with slavery and the abolition movement in the Cincinnati area. The time that Harriet spent in Cincinnati inspired her to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which became a best-seller and catalyst for the anti-slavery movement.

Quote:

“Home is a place not only of strong affections, but of entire unreserved; it is life's undress rehearsal, its backroom, its dressing room, from which we go forth to more careful and guarded intercourse, leaving behind ... cast-off and everyday clothing.” — Harriet Beecher Stowe, as quoted in The Christian Science Monitor, June 13, 2012.

Sources:

Beecher Charles, ed. Autobiography, Correspondence, etc., of Lyman Beecher D.D., Vol. 2. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1865.

http://www.csmonitor.com/Books/2012/0613/Harriet-Beecher-Stowe-10-memorable-quotes-on-her-birthday/Home

The Harriet Beecher Stowe House was the official residence of the Lane Seminary president. Harriet's father, Rev. Lyman Beecher, was the home's first resident.

Rev. Lyman Beecher was a leader in the Second Great Awakening, a Protestant revival movement during the early nineteenth century. This movement brought the Beechers to Cincinnati so that Lyman Beecher could pursue his mission in training ministers at the Lane Seminary to “win the West in Protestantism.” His eldest daugter, Catharine Beecher was a female educator and writer who founded several female high schools and colleges, including the Western Female Institute that was once located in downtown Cincinnati. Lyman Beecher's son Henry Ward Beecher was an American clergyman as well as a social reformer and speaker. He is best known for theological approaches that emphasized God’s love and his support for the abolition of slavery.

Although Harriet married Calvin Stowe in 1836 and moved to a nearby property on the Lane Seminary grounds, she frequently visited her father’s home, and likely gave birth to her first two children in the upstairs bedroom. Harriet and her family lived in Cincinnati for 18 years, and were influenced by their experience with slavery and the abolition movement in the Cincinnati area. The time that Harriet spent in Cincinnati inspired her to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which became a best-seller and catalyst for the anti-slavery movement.

Quote:

“Home is a place not only of strong affections, but of entire unreserved; it is life's undress rehearsal, its backroom, its dressing room, from which we go forth to more careful and guarded intercourse, leaving behind ... cast-off and everyday clothing.” — Harriet Beecher Stowe, as quoted in The Christian Science Monitor, June 13, 2012.

Sources:

Beecher Charles, ed. Autobiography, Correspondence, etc., of Lyman Beecher D.D., Vol. 2. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1865.

http://www.csmonitor.com/Books/2012/0613/Harriet-Beecher-Stowe-10-memorable-quotes-on-her-birthday/Home

A big thank you to Rosie Carpenter, University of Cincinnati student and Harriet Beecher Stowe House intern, for developing the content of this tour.

|

Web Hosting by iPage